M.I. Devine

A BOMB IN A CATHEDRAL

“At the trial of God, we will ask: why did you allow all this?

And the answer will be an echo: why did you allow all this?”

–Ilya Kaminksy, Deaf Republic

November 14, 1940: here’s the church, and here’s the steeple. Here’s Coventry’s medieval cathedral. See the Luftwaffe drop the bombs; see them fall on top of the people.

Or, as an eyewitness told the BBC, a mere fourteen-year-old girl: “I saw a dog running down the street with a child’s arm in its mouth. There were lines of bodies stretched out on blankets.”

Lines of bodies: they make me think of the poet Philip Larkin. Eighteen years old, his lines of poetry. Larkin: this was your town. You saw it go. The end of the old forms (a cathedral), and the birth of the new (lines of bodies).

Even a child can see: Obliteration has its own geometry, its echoes of shape and form.

How does one write among the rubble? How do you even begin to try? Larkin, did you ask the girl: What shall we do with all these lines?

Maybe that’s art. A way to save a world we know will fall apart.

*

I think of another church. Another time.

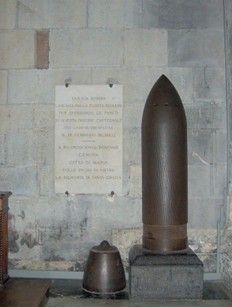

I’m in a cafe in Genoa. Fall, 2019. A tourist, I tour the Italian city’s famous cathedral, Duomo di Genova, Cattedrale di San Lorenzo, and say a prayer to a bomb that stands unexploded there. The British Navy delivered it here three months after Coventry was broken, blown up, and burned. The bomb tore open a wall in the cathedral but did not explode. Call it a miracle. People do. Quiet it stands like a saint in its niche, stands like a sentinel.

(This bomb, launched by the British Navy, though breaking through the walls of this great cathedral, fell here unexploded on February 9, 1941. In perpetual gratitude, Genoa, the City of Mary, desired to engrave in stone the memory of such grace.)

Tonight we hear music.

A band covers Pearl Jam and Italians sing along and we do, too. Things change by not changing at all, sings this Eddie Vedder, in “Elderly Woman Behind the Counter in a Small Town.” And though he’s singing about a woman behind a counter, like a painting by Hopper, I think of forms and how they’re not their former.

And for the first time in a long time that I can remember, I think about how a poem, or a song, is like a bomb that is still a bomb and not a bomb at all. (It’s a miracle.)

The bomb is shaped like the roof of a church, or the shape of your hands forming a steeple.

*

Pray to the unexploded bomb in the Genoa cathedral because it’s a miracle, because it’s a form for measuring time like a sonnet; and it lets time do what time does to every form, which is simply this: It makes forms legible. That’s what happens to forms over time: Change by not changing at all. You read them and read them again and they are not as they were and you are not as you were. All things become new and possible. A sonnet. A bomb. A bomb in a cathedral.

*

Make it new! says Ezra Pound, repeating the Shang dynasty’s first king (1766-1753 BC). Things change by not changing. A modernist manifesto; a slogan on the washbasin of a king.

But here’s the thing: When I think of Larkin at eighteen writing sonnets while a city explodes and the dog makes off with the child’s arm in its mouth and the bodies are lined up and history will not turn, will not turn like a volta, and will not end like a sonnet with the comfort of a couplet, I think of a poet practicing an elegy for form’s failure; the balding young man will write a song of loss for what art cannot save, cannot protect (and maybe never could), no matter its dream, no matter the glory it entertained; I think of him looking up at high windows (which used to be there) and looking higher and even higher; and all that I mean is that I think of poetry of endurance and failure. Endurance and failure. That poets build little rooms in houses on fire: To show you not that it burns but to show you instead the shape of the fire.

*

“The little room of the sonnet serves as an echo chamber and amplifier.” That’s Adam Kirsch. And here’s Larkin, in his famous church, in “Church Going,” the one he enters once “I am sure there is nothing going on”:

Mounting the lectern I peruse a few

Hectoring large-scale verses and pronounce

‘Here endeth’ much more loudly than I’d meant.

The echoes snigger briefly.

Is this the end? The echo chamber of the poem mocks the question. Someone like you has been here before. Has mounted and pronounced more loudly than he meant. Sure, maybe the church, now empty, has changed. But maybe it’s better to set the darkness echoing. Things change by not changing at all.

Or as I put it in my own recent homage to “Church Going” at Literary Matters:

You’d think that absence is one way to know

for sure there’s nothing going on. You’re wrong.

Friedrich Kittler rewrites Barthes: “Record grooves dig the grave of the author.” But it’s surely the other way around: The author turns every grave into a new groove. The needle falls, the echo resounds: yes yes y’all.

Above, you’ll find James Joyce, Michael Robbins, and Seamus Heaney in the queue. But don’t blame me, dear reader; I’m but a discourse network.

(I don’t mean to but I do.)

*

Larkin the teenager trained in the sonnet form, a tutor text for him in how forms change by not changing: little rooms, often literal waiting rooms, where the speaker finds himself in conflict. With time. With the stinging awareness of being human. Human limits.

Larkin’s at his best in bedroom poems like “Aubade” and “Sad Steps,” where he refuses to look at the light (but then doesn’t refuse). Old man poems came to him, more or less, as a teenager. Perhaps he was bemused, and that’s surely not the right word, by his body (a cage), his country (a cage), and his family (ditto). “Why aren’t they screaming?” Larkin asked about the elderly in his fifties. But the question was a selfie of sorts for the poet long before, a ringing in the ears, an echo in his sonnets.

Take, for example, the unpublished “Autobiography at an Air-Station” (1953), a summary of his apprentice years. Airplanes could be triggering for someone who lived through the 1940s, but not here. Here is modern deliverance, its promise and threat, which is just another way to say, in Larkin’s world: Behold, the dream of bureaucracy.

“Autobiography” reminds us the sonnet was “the first lyric form since the fall of the Roman Empire intended not for music or performance but for silent reading. As such, it is the first lyric of self-consciousness, or of the self in conflict.” That’s Paul Oppenheimer in The Birth of the Modern Mind. And here’s Larkin at the airport, waiting, waiting, ordered and orderly, like a modern man: We “sit in steel chairs, buy cigarettes and sweets.”

For Larkin the sonnet is a form for mapping a modern logic onto the page: its coordinates modern forms, like the steel chair, lines of people, lines of bodies, repetition, incomprehensibility, and, of course, quiet rage. Look around, Larkin seems to say, it’s hard to get started, it’s hard to even begin.

Delay, well, travelers must expect

Delay. For how long? No one seems to know.

With all the luggage weighed, the tickets checked,

It can't be long… We amble to and fro,

Sit in steel chairs, buy cigarettes and sweets

And tea, unfold the papers. Ought we to smile,

Perhaps make friends? No: in the race for seats

You’re best alone. Friendship is not worth while.

No “I” is present here. You’re a traveler, you’re at their (whose?) mercy, and, please, try not to make a fuss. There’s a way of doing things, you guess (though no one seems to really know).

The English sonnet is a way of doing things: proxy for safety and a semblance of order that always in Larkin unravels. “We” gives way soon enough, questions pile up, and delaying caesuras of each line finally hit a roadblock “No” in line seven right at the sonnet’s turn.

Sonnets of the air are not such rare birds. There’s W.B. Yeats’s “Leda and the Swan.” Like Yeats, Larkin opts for an Italian sestet (efg/efg) to advance the second part in a poem where no one goes anywhere at all. It’s how you make things fall apart, in a way, or do what bombs do by undoing what we think can’t be undone. From English to Italian form, Larkin plays with forms, to unspool, disrupt, and scramble. What, exactly? Hope for progress: for comfort, closure, the couplet. Lines of words, lines of bodies that might go somewhere turn instead into dimmer and dimmer versions of themselves, echoes like a stepping into sleep, into darkness, into night. Couple(t)s get erased, grow distant, paler. “The thousands of marriages,” writes Larkin elsewhere, “lasting a little while longer.”

What do you do in the face of this?

Delay, delay: That is the name of the modern game after all. The machine breaks down. Delay. Delay. Repetition as endlessness, as alienation. “Literature,” writes Chris Forster in Modernism and Its Media, “is that which is expunged from the bureaucratized realms….”

But what if lines can overcome lines through lines? What if, in the poet’s hands, the old forms help us discover something new? Something true?

To put it another way: morning is coming, light is breaking. And the poem becomes a form to beat them at their own game. Art makes nothing happen, the lines of bodies stay lines of bodies, but can it at least help you save your life? Is that too much to ask? Perhaps. But you can give it a shot.

What’s it mean to delay, to write a sonnet, to create, to find a new groove, when you know you can’t make anything stop? No one seems to know how, seems to know anything at all. But still we try and in trying try to keep it all at bay. We wait for it. We write in handcuffs. We live that way.

*

Old things turn into something new, a bomb, a sonnet, a cathedral. Forms, it’s true, can parody what we think we can get out of them (protection, security) in a world where fire drops from the sky and no one, not one person is safe. The dog runs down the street and takes the child’s arm away. The little girl sees it all.

Bodies line the street, parody of geometry.

Larkin’s is a poetry of killing time, in every sense of the word. Of course, that’s what art does. Here comes the morning, and another day. The sonnet, in Larkin’s hand, becomes an app for measuring that: anticipating, remembering, dreading, forgetting. Ignoring. Is there a better definition of art? It’s a way of enduring.

In Larkin’s “Autobiography at an Air-Station,” life is a race for seats, the looking ahead to your own transcendence, your flight, the god-machine that will ravish you, salvage you, transform you, the modern form that will snatch you up like a swan.

No. No such luck.

Here’s the volta, the sonnet’s turn into, what else?, time and what ifs.

Six hours pass: if I’d gone by boat last night

I’d be there now. Well, it’s too late for that.

The kiosk girl is yawning. I feel staled,

Stupified, by inaction - and, as light

Begins to ebb outside, by fear; I set

So much on this Assumption. Now it’s failed.

We’re brought through the sestet into the sixth hour of delay; six lines are left, and you’re at sixes (and then at sevens). We are in real time here, not unlike waking at 4 a.m. in “Sad Steps” in line four of the poem (“Four o’clock: wedge shadowed gardens lie / Under a cavernous, a wind-picked sky”).

Aubade: obey. Time is a cage, and this preoccupies Larkin from his teen years to his final “Aubade,” half a century, the idea of time and form, art as a system of deliverables that never quite does deliver. But it tries. Endures. Measures. Waits for. We wait for what, precisely?

Darkness swarms; travelers yawn; the doodling poet, feeling “staled,” will repeat the theme of time’s chains that hold him fast for the rest of his career:

I set

So much on this Assumption. Now it’s failed.

It’s a powerful conclusion in “Autobiography,” no doubt, like Stevie Smith’s own famous ending for her most famous poem, “I was much too far out all my life / And not waving but drowning.” Larkin, raised among ruins that were once for prayer, and high windows (that used to be there), knew something about endings.

*

His critical writing, mostly, is a fight for formal bonds that bind us together in mutual survival and struggle. He’s against those who are against that. It’s why he elegizes (the past? churches? belief?) in “Church Going,” and why you feel a sonnet haunting “Sad Steps,” which takes, it turns out, its title from a sonnet by Sidney.

Though he’d soon leave the sonnet behind, too practiced in its deflations and counterpoints, it’s where he learned to measure time, lighten its weight, and wait for the light.

Both Larkin and poetic forms–the tradition passed down to us; in short, what we can do with lines–grew up and were revised in a time of war. It’s important to remember that. How fire fell from air. How high windows were windows that were no longer there. It’s important to remember that. Every poem is a cathedral with its unexploded bomb–like a saint in a niche. In “Autobiography,” nothing happens, which is what’s most terrifying. There is no sudden realization. No explosion. No apparition at the air-station. Or not yet.

To write in form today is merely–is always and only–to be a self calling out, “Here endeth.” Maybe it’s what it’s like to be a bat. (Robbins, again, real quick: “Augustine cautions against taking this / literally… // But still. What’s it like to be a bat?”). To sound the depths. To echolocate. Or maybe a bomb. Like bombs, we seek to declare, pronounce, decide, and destroy. To say life ends at death like that is it. And we call out, we call out much louder than we thought. That we might be louder than bombs. Here endeth. That’s the kind of poem I want to read. Here endeth. And that’s the kind of poem I want to write. A poem that’s tragic, for sure, something to grow wise in. After all, the echo says, “death.” Here endeth: the echo says “death.” But no (here’s the volta): I want a poem that’s not just tragic, but something more, something grander, stranger, funnier, wilder, something deeply obsolete, which is to say, true. Because somewhere someone–a child, a witness, a poet–will forever be surprised by a hunger that “Here endeth” is not enough. That it simply will not–cannot, must not–do.

M.I. Devine is the author of Warhol's Mother's Pantry, winner of the Gournay prize. He is co-founder of the avant-pop project Famous Letter Writer, which releases DADAMAMA in 2025-2026. His poetry has appeared recently in Literary Matters and Nimrod International Journal, and a selection from a new memoir project will soon appear in Image. (www.midevine.com)