Issue PDF

Poetry

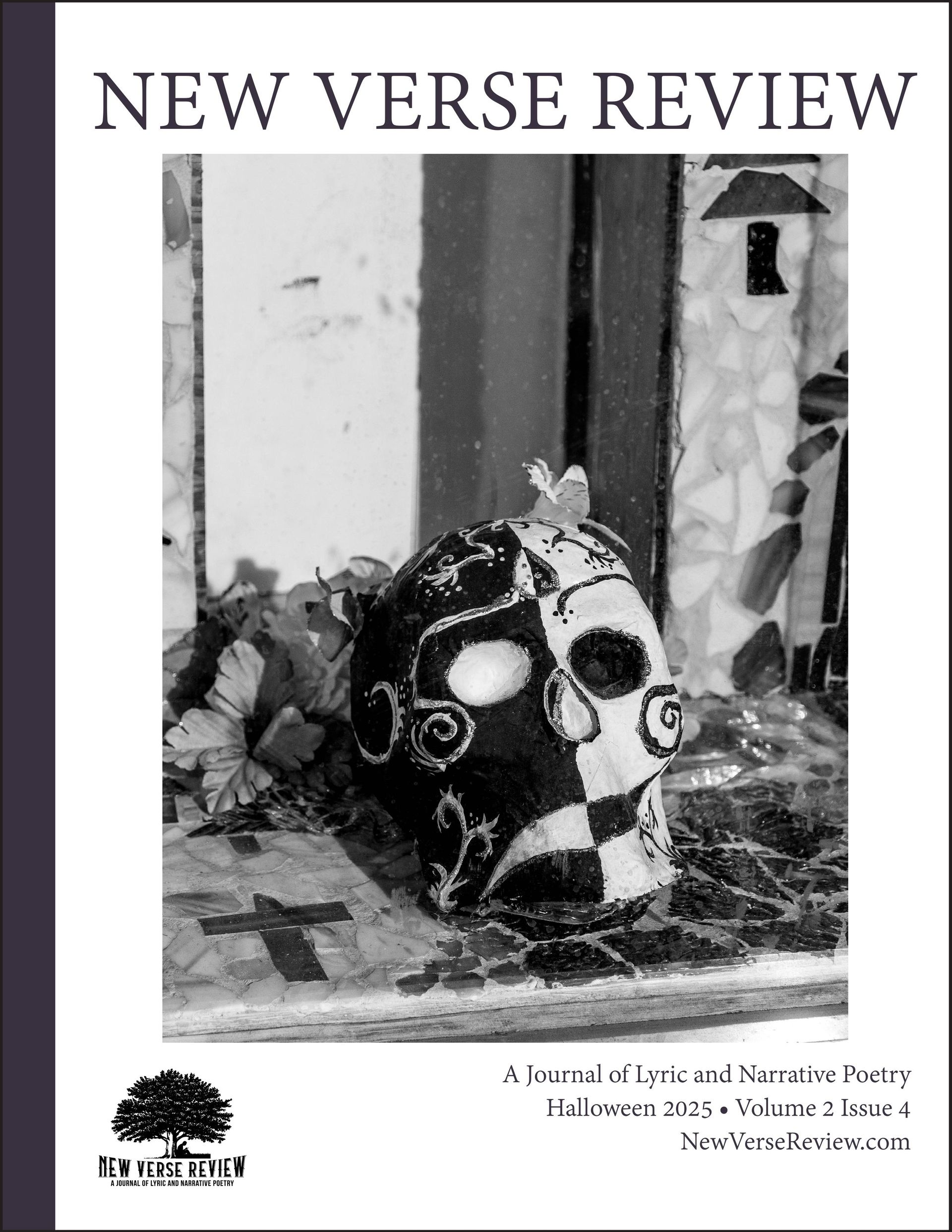

New Verse Review 2.4:

Halloween 2025 Mini-Issue

ISSN: 3068-1766

Edited by Steven Knepper and Zina Gomez-Liss

Marly Youmans, "The Night Float"

Hilary Biehl, "Danse Macabre"

T. O. Brandon, "Universal Monsters"

A. Z. Foreman, "Odin in the Gallows-Wind"

Katie Hartsock, "Scylla Names Her Dogs"

Vince Gotera, "Happy Halloween Surprise" and "Flight on All Hallows' Eve"

Luca D'Anselmi, "Relic"

Jesse Keith Butler, from "The Voyage of Saint Brendan"

Meredith Bergmann, "The Witch of Grove Street"

Brian Palmer, "Ode to Words to a Ghost on Halloween"

Angela Alaimo O'Donnell, "The Reader"

Kelly Scott Franklin, "Romantic Lines Written on the West Yorkshire Moors"

Liz Cambra, "San Francisco's Fourth Female Detective Speaks"

Elijah Perseus Blumov, "Spelunker"

Nicole Yurcaba, "It is Apple-Picking Season & You Cannot Help"

David Southward, "To Autumn, the Stripper"

Timothy Kleiser, "Kentucky Katabasis, or Friday at the Wildcat"

Sunil Iyengar, "Southern Gothic"

J. M. Jordan, "Incident on the St. John's River"

Mattie Quesenberry Smith, "Autumn, Without Her Healing Hands"

Helena Feder, "Camouflaged"

John Poch, "Lunatic"

Jared Carter, "November"

Marly Youmans

The Night Float

The trionfo, pulled by oxen, was a very large carro,

black all over and painted with the bones of the dead

and with white crosses. On top of the carro was a huge

figure of Death with a scythe.

—Giorgio Vasari

Enormous axles churned the wagon wheels

That like the wide but low-roofed tomb on top

Were stained to black, while seven golden seals

Dangled from a jet-dyed leather strop.

Trembling on the shaft between the oxen,

A wooden angel clasped a gleaming horn.

Death scattered smiles from jaws smeared with toxin;

Each rose around his neck was slashed by a thorn.

When torches lit the riders bearing skulls

On crooked staves, and the nags that might be dead,

The city shrieked like rabbits, shrilled like gulls,

And keened like wolves, exulting in its dread.

The horsemen’s plainsong shivered through the smoke;

The oxen groaned and strained against the yoke.

Marly Youmans is the author of sixteen books of poetry and fiction. Recent work includes a long poem, Seren of the Wildwood (Wiseblood), a novel, Charis in the World of Wonders (Ignatius), and a poetry collection, The Book of the Red King (Phoenicia).

Hilary Biehl

Danse Macabre

A tritone on the violin. A thin

white hand on which the wedding band won’t stay

leads to an arm, then to a lipless grin—

an invitation to the cabaret.

Marquee lights glitter. The celebrities

are stunned as we are. Remnants of their gray

hair cling like cobweb to the limbs of trees

as each of them is nimbly whirled away.

A politician waltzes stiffly past,

half-leaning on his partner. Birds of prey

are lazily appraising us. At last

the orchestra picks up the Dies Irae.

Hilary Biehl's poems have appeared in Blue Unicorn, THINK, Able Muse, and elsewhere. Her first poetry collection, Giants Crossing, is forthcoming from Kelsay Books. She lives in New Mexico.

T. O. Brandon

Universal Monsters

I. Frankenstein

There is no body but body, no soul

But voltage-wracked neuronal stalks, no life

But matter coiled in damp entropic folds,

No secret not a subject for the knife.

I dreamed I made a monument to man,

From bone and sinew stitched, through art refined,

A living body built on Reason’s plan,

Mind’s mirror in a self-created mind.

I woke to find these Arctic floes, these wild

And iterating sheets of ice, and heard,

As if from ice, that voice: my voice, my child,

The brilliant, cruel, and patchwork thing I made:

“Prometheus, who mocks the soul’s design,

Your monster lives. Your voice, your name, are mine.”

II. Dracula

Because I cannot taste the blood, I need

The blood, because I cannot bleed, I thirst

For blood, because I cannot live, I breed

In blood the old contagion’s carnal curse:

The self-consuming self-regard so vast

That it withholds its image from the mirror,

Yet seeks itself in every mirror, and casts

Long shadows out to feast on lust and fear.

This hunger makes a wasteland of my life,

An emptiness inscribed with fang and blood.

Immured within the castle of myself,

I only feel those things so pure they flood

The barren, ingrown deserts of my loss:

The greenwood stake, the rising sun, the Cross.

III. The Mummy

My wealth made all arrangements: mourners cried,

The priests filled carved canopic jars and bade

The salt preserve my flesh, the gods provide

Eternal life beyond the pyramid.

My slaves would fall to dust, my strangled wife

Would worship me as wisps of hair and bone,

While I, immortal, ruled from Pharaoh’s throne:

A god on earth, a god in afterlife.

A man who seemed Osiris turned me back.

He pointed to the scales that told my doom,

Then cursed this golden crypt to endless dark.

Know this, who claims the treasure of my tomb,

Who seeks immortal singularity:

You find it here. You find hell. You find me.

T. O. Brandon is a writer and educator who lives in Nashville, Tennessee. His poetry has appeared in New Verse Review and Literary Matters. He was awarded first place in the 2025 First Things Annual Poetry Prize.

A. Z. Foreman

Odin in the Gallows Wind

Nine nights I hung, and no one cut me down.

The wind unspooled my breath like woven thread.

I watched the stars ignite the ash-tree's crown

and learned the speech that only speaks the dead.

The tongue I drank was neither strange nor kin—

it burned like nettle-broth inside my brain.

Its words were antler-etched in runes. Its din

held swords of sound and silence soaked with pain.

The dead men gave me gifts beyond their telling:

the mead of madness, and the mind of crows.

A wolf awaits. The womb of fate is swelling.

A spear of ash through all nine kingdoms goes.

I gave one eye to see the shape of things.

Now crows are crowned, and fire fathers kings.

A. Z. Foreman is a linguist, poet, short story author, and/or translator currently pursuing a doctorate at the Ohio State University. His work has been featured in the

Threepenny Review, ANMLY, The Los Angeles Review, and elsewhere but not yet

The Starfleet Academy Quarterly. He wants to pet your dog.

Katie Hartsock

Scylla Names Her Dogs

How will we eat,

I wondered like

a woman, the first

to wake that morning

after, and without

thinking, within

what a lonely body

spiraled with strange

absences

and stranger excess,

I pet one’s head.

To me it was

not me, but when

she slightly stirred,

her jaw a bit lax,

and leaned her ear

towards my touch,

I felt the comfort

and the satisfaction, too—

a scratch that reveals

the itch. I’d assumed

they all were she’s:

risen from my thighs,

so fierce at first

they would have bitten

each other’s ears

or my unhinged hands

but for some instinct

they’d feel the sting.

Now all our teeth

taste a single hunger.

I did not want

a lover; I’ll never

run or have to run again.

Now it is we

who chase, though that

first day we were a mess.

I was trying to get us

to some vague idea

of cave, and swimming

did not go well.

One got hit

in the face with a wave

and choked, and whimpered.

And I said It’ll be

OK, come on.

Now we glide—

nautiline,

lemuriate,

intertidal,

abyssal, pelagic.

Gorgo has the bloodhound nose:

if she sniffs,

something’s coming.

Missy, my half-wolf

keeps watch all night

and sleeps while the rest

of us work the day.

Chariot leans

his shepherd’s head

against my belly

button, just

where fur pivots to skin,

gazing up at me

with such eyes, am

I crazy or do

they look like mine?

Katie Hartsock's second poetry collection,

Wolf Trees (Able Muse), received the Philip H. McMath Poetry Prize and was one of Kirkus Review's Best Indie Books of 2023. Her work appears in journals such as

Ecotone, Prairie Schooner, At Length, Iron Horse Literary Review, Image, and

RHINO. A chapbook,

Love-Gifts To Be Delivered via Subterranean Rivers, is forthcoming from Aureole Press. She is an associate professor of English and Creative Writing at Oakland University in Michigan, and lives in Ann Arbor with her family.

Vince Gotera

These two sonnets are from a novel-in-poems about two aswang (mythical Philippine monsters) who fall in love—she a vampire, he a werebeast who shapeshifts into a huge dog—and try to live like normal people, in plain sight. The two lovers marry and move to the US, where they birth a son. At this point in the novel, the husband Santiago has passed away. In the first poem, Clara is reminiscing about the time before when she was pregnant and her husband and she had an unusual Halloween experience.

Happy Halloween Surprise

—Pushkin sonnet

Clara lay in bed recalling

Tiyago in much happier times,

memories that had her smiling,

pranks and little harmless crimes.

One Halloween when she was pregnant

the two imagined themselves as parents

taking their little one on the streets

of San Francisco: trick or treat.

Tiyago shifted into his canine

form, as big as a Great Dane,

and out they went, dog and dame,

taking a stroll in the moonshine.

Laughing children gathered around

in costume, petting her lovely hound.

In the second poem, Clara and Santiago's son Malcolm (himself an aswang) celebrates Halloween unlike his schoolmates trick-or-treating.

Flight on All Hallows’ Eve

Malcolm, at the close of his first decade,

strolled twilight sidewalks of San Francisco.

On his chest, ensconced in a yellow shield,

a bright S—red blood of HesuKristo—

balanced by a tight suit of blue sapphire,

soft velvet tints of the Virgin Mother.

A boy’s homemade costume for Halloween,

the ultimate war hero: Superman.

But our boy was not playing trick or treat.

From underneath Malcolm’s billowing cape

blossomed moth wings. Malcolm slowly climbed up

into clear sky, with soft fuzzy wingbeats.

Like his Mom and Dad on their honeymoon,

he soared, glided, over darkling ocean.

Vince Gotera

is Poet Laureate of Iowa. He was editor of the

North American Review and

Star*Line. Poetry collections:

Dragonfly, Ghost Wars, Fighting Kite, The Coolest Month, Dragons & Rayguns. Recent poems:

Crab Orchard Review, Philippines Graphic, Rattle, Multiverse, and

Hay(na)ku 15. Blog:

The Man with the Blue Guitar (http://vincegotera.blogspot.com).

Luca D'Anselmi

Relic

I saw the widow kneel by the altar rail,

take a severed finger from a handkerchief,

and press it to her lips. Then the old priest

intoned a gospel: “In those days a girl

taught Peter how to read by writing verse

about a fisherman who wouldn’t die

although for weeks he was left crucified

feet up, until his chest grew thick with grass.

And from his mouth a spring of water flowed

out over his eyes, babbling down to fill

dusty cisterns at the foot of the hill.

Mouthing through syllables, Peter didn’t know

the verses prophesied that his great love

would never fail.” But when the widow put

the finger down beside her on the seat

I thought it twitched, and then I saw it move

on the cushion like an inchworm, and I knew

that what they say about the saints is true.

Luca D'Anselmi holds a Ph.D. in Classics from Bryn Mawr College and teaches Latin and Greek language and literature. His poetry has recently appeared in The Hopkins Review, Empty House Press, and Ekstasis, and has been featured in Poetry Daily.

Jesse Keith Butler

From "The Voyage of Saint Brendan"

Translated from the Middle English text in the South English Legendary (lines 401-438)

These holy men sailed forth, whatever way God’s favour fell.

Because God’s grace was with them, they all traveled very well.

One time, when they were sailing through a tempest, a prodigious

sea creature started chasing them. The thing was huge and hideous.

The beast spewed burning foam out from its mouth and nose. Each blast

sent reeking spume above the ship—so high it cleared the mast.

Ungainly as a house, the monster barrelled after them

astonishingly fast, the whole time belching brimstone phlegm.

The frightened monks cried to Saint Brendan—also to Christ Jesus—

“Please bring us help! That monstrous beast is just about to seize us!”

And when the monks had given up all hope of their survival,

another fish swam from the west and smote into his rival

with such sea-splitting speed that the great monster’s ghastly carcass

was ripped apart. Three fragments drifted down into the darkness.

The fish swerved through the sea and swam back swiftly westward. They

gave joyful thanks to Jesus as they watched it swim away.

From there, these holy men sailed on the sea so long that hunger

set in as their supplies ran out. When they could last no longer,

a little bird flew to them very swiftly, bringing them

a branch with grapes of perfect redness bunched on every stem.

He brought them to Saint Brendan, who received the grapes with laughter.

They feasted and had food enough for fourteen nights thereafter.

But when the grapes were eaten up, their hunger was renewed

until at last they saw an island where they could find food.

That island swayed with lovely trees—each tree so full of grapes

that all their branches hung down to the ground like heavy drapes.

Saint Brendan landed on the island and, with no delays,

he filled their ship so full of grapes they lasted forty days.

Soon after that a monstrous griffin flew across the waves

and pounced upon their boat as if to plunge them to their graves.

The monks cried out in fear and thought their deaths were all assured.

Then something else came flying up—it was the little bird

they knew, come from the Paradise of Birds straight on a course

to intercept the monster. The bird struck it with such force

that the griffin flailed back from their vessel—gladdening Saint Brendan.

The bird in one blow gouged out both the beast’s eyes to the tendon.

The eyeballs plopped into the sea, soon followed by the griffin.

There’s nothing that can kill the man whom God wants to keep living.

Jesse Keith Butler was the winner of the inaugural 2024 ESU Formal Verse Contest and will be a 2026 Writer in Residence at Berton House in Dawson City, Yukon. His first book, The Living Law (Darkly Bright Press, 2024), is available wherever books are sold. Learn more at www.jessekeithbutler.ca.

Meredith Bergmann

The Witch of Grove Street

A block from school her weeping mulberry

dropped berries, reddening the clean concrete.

The tree was practically in the street.

In memory, its berries taste of glee

and daring mischief, sweet as party punch.

Erupting from her door to scatter us,

she seemed much larger than her small frame house,

and we ran gasping home to get our lunch.

But not before we called her names. “Old witch”

was probably the worst. I know she heard

and hated. We loved the weapon of the word.

We loved to cut each other with a switch

of epithet, a curse. She has no face,

in memory. The mulberry, its bare,

contorted winter branches gnarled to scare,

and its imbedded scowl, will take that place.

I see gray hair, as mine has turned. And how

a twist of woodwork fit like cobweb in

the gable of her door. She’s fast, and thin.

Why must I see her in my mirror now?

As if her tree, its gothic attributes,

are now engraved in my expression,

stripped of its sweetness, forcing me to question

how I will best protect my fragile fruits.

Meredith Bergmann is an award-winning sculptor with public monuments in New York, Boston, and beyond. Her poetry and criticism have appeared in many journals including Barrow Street, Contemporary Poetry Review, Hopkins Review, Hudson Review, The New Criterion, Tri Quarterly Review, and the anthologies Hot Sonnets, Love Affairs at the Villa Nelle, Alongside We Travel: Contemporary Poets on Autism, and Powow River Poets Anthology II. She was poetry editor of American Arts Quarterly from 2006-2017. Her chapbook A Special Education was published in 2014 by EXOT Books, and her self-illustrated book The Dying Flush was published by EXOT in 2024. She has won three Honorable Mentions from the Frost Farm Poetry Prize and a 2nd prize from the Connecticut Poetry Club. Bergmann has taught ekphrastic poetry workshops at the Frost Farm, Poetry by the Sea, and Writing the Rockies conferences.

Brian Palmer

Ode to Words to a Ghost on Halloween

After John Keats (b. Oct. 31, 1795)

Full soon thy Soul shall have her earthly freight,

And custom lie upon thee with a weight,

Heavy as frost, and deep almost as life!

—William Wordsworth, “Ode to Intimations of Immortality from

Recollections of Early Childhood”

A ghost—my son in shrouds—and I, mid-fall,

(as I, a mortal, walk along, he floats)

head homeward down a side street, Avenal

(a Spanish word, in English “field of oats.”)

It’s Halloween, and we’re alone, out late,

where all is dark except this haint blue street.

The wind turns shapes to shades, and time

to dry, light whispers, but my soul and feet

are leaden, heavy, so I lift the weight

with words out loud and lighten them with rhyme.

In praising the awaiting, dark abyss

for those with lives half-lived now gone to graves,

and too, of those who never found the bliss

in understanding how, in life, love saves

us from despair and toil, I slake the gloom

the half-moon makes that tries to take my breath;

my words—before I’ve “glean’d my teeming brain,”

which left unsewn to wither in the tomb

of night and leave a fallow field, like death—

can fill the stores with reaped now ripened grain.

We pass a pond, and he imagines mirrored

there in jointed cottonwoods that grasp

the guttering of the half-phased moon, some feared

bone fingers reaching out, a drowning gasp,

a child snatched back into that cold, black place.

My fear turns to praise, as it gives souls

still gleaming new their passion and their pride

to take their lot, and as do roses, race

to bloom, despite the quick dead ends: the holes

filled soon with their pale petals, cut and dried;

and drives those working long their rows with weird

unease to gather days in bales, do tasks

that left undone means ruin, amid the sheer

terror of finding nature just a mask

on vacancy, their energies a waste,

with no celestial past terrestrial; so

they follow owls to hollow trees for dryads’

earthbound spells to keep the candles placed

inside their jack-o-lantern heads lit, cold

beneath the often-vaunted vault of sky.

I praise the ache that makes the pulse, and more

how full the living seasons set by dying;

at October’s end, I ask the one core

question—though it waves, though time is flying,

though tricky as a 31’s 13—:

Does Death lie at this night’s true heart or Life?

The answer: void as foil to souls and saints

(Both hollow and is hallowed, Halloween);

matched worth to those unstained and free of strife

and those in hell amending their constraints.

Near home, his cosmic form, so white three hours

ago has gathered earth along its hem:

hulls and husks and feathers, dirt, old flowers. . . .

I’ve faced some doubts with words in singing them,

as he, while losing his immortal coil,

imprints on me, his father, flesh and blood.

We go then two alive down Avenal.

Above the oats, our voices float, mid-fall.

And as this Halloween I’ve sung the flood

of airy fears, new life stirs in the soil.

Brian Palmer is inspired by the natural world which continues to have a formative effect on his life and poetry. His recent chapbook Prairiehead was released in 2023. His work appears regularly in various journals, and he is the editor of the literary journal THINK. He lives in Juneau, Alaska.

Angela Alaimo O'Donnell

The Reader

For Patrick

Early on, you knew that knowing mattered.

The books on our shelves held worlds you desired.

You a toddler, my attention scattered,

pored over pages that set you on fire

with horror—Blake’s Dante haunted your dreams,

his sinners writhed in their scorching flames.

Poe’s tell-tale corpses made life seem

uncertain, at best. This was no game

as other—unread—children might think.

You were serious so young, understood

the truths spelled out in indelible ink.

All your life you tried to be good.

While others rode bikes, played whiffle ball,

you heard Dante’s souls and Poe’s bodies call.

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, PhD, is a professor, poet, scholar, and writer at Fordham University, where she serves as Associate Director of the Curran Center for American Catholic Studies. Her publications include two chapbooks and nine full-length collections of poems. Her book Holy Land (2022) won the Paraclete Press Poetry Prize. O’Donnell’s eleventh book of poems, Dear Dante, was published in Spring 2024. She is currently at work on the manuscripts of two new collections, one tentatively titled Body Songs, poems on embodiment, and The View from Childhood, poems about family, coming of age, and the place(s) we call home.

Kelly Scott Franklin

Romantic Lines Written on the West Yorkshire Moors

Why must you be so cold, my Catherine dear?

I’ve loved you more than any lover can,

but now you’re hard to get. What’s there to fear?

Byronic moodiness? My Gypsy tan?

You used to love me, dearest: why the switch?

Is it that nagging question of my class?

But we were kids together! Now I’m rich!

And sure, you’re married—let such trifles pass.

I miss your sympathy, our childhood dreams,

the lonely walks together on the moor.

The smile that graced your lips has died, it seems,

and you’ve become much graver than before.

Night after night, I lie there next to you;

you’re pale and still; you never speak to me.

What’s come between us? Tell me darling. Do.

—Your loving Heathcliff, for Eternity.

Kelly Scott Franklin's poems, translations, essays, and reviews have appeared in Hopkins Review (forthcoming), Nimrod, Able Muse Review, Literary Matters, New Verse Review, The Wall Street Journal, Commonweal Magazine, and elsewhere. He teaches at Hillsdale College and lives in Michigan with his wife and daughters.

Liz Cambra

San Francisco's Fourth Female Detective Speaks

Police have always been hiring plain women

in Sunday best to follow pickpockets, befriend

the boarding house matron’s brother, but once

you chase down enough men in windowpane

jackets, crush them in the sides with your side

pistol, in full swing of All Saints Day mass,

any decent shopkeeper won't have you.

Secretarial work? Forget about it. Milliner? As if.

And there you have it: mine’s the face the troubled

sergeant configures, when a debutante’s fiancé

expires after a night of a warm gin—that’s Tuesday.

And a new pair of leather shoes, a German chocolate

cake, and 2 cents for the coffee can above the sink.

That couch? An old lecher changing an awful pleated

lampshade—ZAP! An electrical surge turned

his adulterous hand black. I make it sound like a load

of flimflam, but be assured, I can pause and take

the eternal note of sadness in: poor lamp, poor

charred hand, poor second wife who should

have fed her husband nicotine instead of wasting it

on the roses. In those early years I wouldn’t have

noticed. Now I notice everything, can find

the Czarina’s lost emeralds in a pot of clam chowder

with enough time to tweezer the clams from the clasp,

time enough to see the stones set against my second-best

turtleneck, before chucking them off to the sergeant.

At times it's dangerous, I admit. Once, I pissed myself

all over a real nice satin slip, after that arms dealer

threw me in the cellar with his sister’s corpse. Her eyes,

as you know, cleaned out with one of those delectable

little sugar spoons—that’s why my radio is always on,

I mean, if you like the work it's good to have a way

to fidget the attention, to sleep. But the job has its glamour

for sure. A paid night at the opera in gray mink

and a diamanté crown. Was it the soprano or the violinist

who killed the idiot baritone? One more night of Puccini

and I swear I’ll tell you! One more night after that and I might forget

myself entirely. In fact, I almost did once, holed up among

the stout members of the Daffodil Society. It was all

especially cheerful, if you don’t count all the cut up fingers

in the Dutch garden. That autumn, I spent hours in the sun,

digging holes, then dropping in bulbs the hue and heft

of walnuts. I could stand tea with those broads again,

could stomach another chat about the off-color of a rare

double bloomer, learn to be afraid of ice, afraid for flowers—

but it's no use going back after you’ve arrested the head matron

for murder. I spent the remainder of that afternoon

in my gardener’s costume: the flannel dress of an ordinary

hobbyist, but with a sturdier boot, a pair of elbow-high

leather gloves careening out a deep pocket. I just stood

in my room like that, near the window, looking out.

I had been pretending a long time.

Liz Cambra is a Pushcart Prize nominee. Her poetry appears or is forthcoming in Smartish Pace, Entrance, Dunce Codex, Thrush, and others. Her chapbook Flora was published by dancing girl press in 2023.

Elijah Perseus Blumov

Spelunker

I sought the depths, and found them.

Down through the bowels of the world

I crawled toward some new birth.

Where was my terror then?

Perhaps all courage comes

when imagination fails.

But yes, I witnessed wonders.

I saw how drops of wet

attain, over dark eons,

to obelisks of gods

whose names we cannot know,

and anti-obelisks

like anglers’ teeth. I saw,

as I became a worm

through dank intestinal stone,

what unflappable life can do

bereft of dreams of light.

Here among the pale,

mucus-drenched, and blind,

and bioluminescent

galaxies of larvae,

the monstrous thing was I,

who felt that he belonged

only where he did not.

And when, after I fell—

following a glimmer—

fell wedged in this black rift

where none will find my bones—

hopeless miles of rock

above me and below—

after I screamed a hundred

pointless screams, and writhed

until my limbs were flayed

quite pointlessly, I laughed.

Stuck, like a little piggy.

And I laugh and laugh because

despite the long unthinkable

hours left to die,

I knew now I had found

what I had come here seeking.

Elijah Perseus Blumov is a poet, critic, and host of the poetry analysis podcast, Versecraft. His work has been featured in or is forthcoming from publications such as Image Journal, Literary Matters, Marginalia Review of Books, Birmingham Poetry Review, Modern Age, and others. He lives in Chicago.

Nicole Yurcaba

It Is Apple-Picking Season & You Cannot Help

I.

but remember lying on a hay wagon

as your dead lover drove an old blue Ford tractor

the two of you headed into the orchard

to pick pink ladies & his young dog Copper

a kind of heaven beside you your hand in his brown fur

& you told yourself you’d never seen such blue skies

but then you recalled Kyiv in August & you decided

Yes. Yes. I’ve seen bluer & more beautiful skies

& the wagon bounced your dead lover

looked over his shoulder grinned the rut

in the road now past he flipped you

the middle finger & you returned

the favor

II.

soon there will be breaking benjamin’s “so cold”

soon there will be dwight yoakam’s “if there was a way”

there will be led zeppelin’s “hey hey what can i do?”

& there will be the moment you tuck his folded photo into a baltimore sidewalk’s

crack

soon there will be system of a down’s “spiders”

soon there will be alice in chains’ “black gives way to blue”

there will be wagner’s “ride of the valkyries” spinning on the turntable

& there will be the match you ignite & place at the edge of his final letter

& there will be a gust of wind & you will whisper

til’ Valhalla

& there will be muddy waters’ “mannish boy”

& there will be the curling backroads you will never drive again

& there will be the sleepless nights that leave you shattered

III.

somewhere in a lockbox

is an

ikon

you had blessed at saint sophia’s

somewhere at a rural post office

is a dead-letter box he kept

somewhere beneath a loose attic floorboard

is a fading photo of you standing in a Kherson rose garden

somewhere in the orchard

his family spread his ashes & never told you the date, the time, the place

somewhere in the cosmos

he & your father take their poles:

they sit beside still waters

their rods bend

the creature they pull from the abyss

is you

IV.

There is the nothing & there is the everything.

There is the beginning & there is the end.

There is the letter & there is the page.

There is the unpruned orchard & there is the unplowed field.

& there is this season which arrives again

again

again:

before sleep finds you, you hear the plunk

of fruit in wooden crates & your dead lover shouting

Hey, girl! I did you a favor!

as he holds a thick, squirming black snake

with one hand by its tail

Nicole Yurcaba (Нікола Юрцаба) is a Ukrainian American of Hutsul/Lemko origin. Her poems and reviews have appeared in Appalachian Heritage, Atlanta Review, Seneca Review, New Eastern Europe, Euromaidan Press, Chytomo, and The New Voice of Ukraine. Her poetry collection, The Pale Goth, is available from Alien Buddha Press.

David Southward

To Autumn, the Stripper

after Keats

Swiller of fifths and dance-pole votaress,

Big-bosomed friend of the proprietor’s son;

Conspiring with him how to peel a dress

In ways that make the bachelors’ pulses run;

To bend without dislocating your knees,

And fill all seats with bikers guzzling Coors;

To wean plump Hazel off the zinfandels

Bought by a colonel, who keeps shouting “More”

And still “More!” Lately, life’s become your tease;

You smoke in bed and swear you’ve had no peace

Since Summer (that bitch!) ran off with some rich swell.

Who hasn’t seen you often looking bored?

Sometimes whoever seeks a broad may find

You, lying facedown on the barroom floor,

Your wig half shifted—freely breaking wind;

Or in the back seat, snoring; a sound sleep

Dashed when a tow-hook clamping on your truck

Scares you near pissless. (Goddamn whiskey sours!)

And microfiber G-strings sometimes keep

Steadily riding up your tush’s nook;

Or while your press-ons dry, with time to pluck,

You binge-watch Cops and tweeze your brows for hours.

A roommate’s mattress-springs screech night and day?

Think not of them, yours had their music too,—

While strobe lights blur the hands of creeps who pay

To graze your stubbled loin with ice-cold brew,

Then in a wailful choir the Spice Girls mourn:

I’m giving you everything. Your heart goes soft;

A cloud of Aqua Velva stings your eyes;

As full-grown men cheer on live-streaming porn,

Your ears ring; now your balance is thrown off,

A redneck whistles from the crowd to scoff

at Summer’s glitter, falling from your thighs.

David Southward teaches in the Honors College at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. His collections include Queer Physics (Kelsay Books, 2025), Bachelor’s Buttons (Kelsay Books, 2020), and Apocrypha (Wipf & Stock, 2018). David resides in Milwaukee with his husband, Geoff, and their two beagles. Read more at davidsouthward.com.

Timothy Kleiser

Kentucky Katabasis, or Friday at the Wildcat

My smile’s a silver dollar

I’ll flash into your eyes

to make your troubles smaller,

to fill you up with lies.

My word’s a silver dollar

I’ll tumble in your ear,

in my honey-bourbon drawl or

whatever slakes your fear.

My tongue’s a silver dollar

I’ll slide around your tongue

and slip beneath your collar.

I’ll make you feel so young.

My hand’s a silver dollar

I’ll trace along your thigh,

to make your insides holler,

so you won’t ask me why

I give away each dollar.

The Ferryman knows well.

He’s coming on his trawler.

I’ll pay your way to hell.

Timothy Kleiser teaches philosophy and literature in Louisville, Kentucky. More of his poetry appears in Atlanta Review, Literary Matters, Able Muse, Appalachian Review, THINK, and elsewhere. He holds an MFA in poetry from the University of St. Thomas, Houston.

Sunil Iyengar

Southern Gothic

A knot of tourists in the park

are waiting for the guide to show.

It’s nearly midnight, but the dark

promises all who stay will know

of old town evils in due course

and come away illuminated.

Each clan subjected to a curse—

its family line snuffed out, or fated

to yield descendants who went mad—

all this will soon be manifest

in anecdotes the town once had

thought unseemly for a guest.

The benches claim both old and young:

couples whose hands slope in a V

between them, as if here among

the dilettantes, a mystery

remained suspended—one per pair.

Others, impatient, check their phones.

Around them all, the drooping hair

of Spanish moss, and cobblestones

that catch the moon before it flies.

No cars. Only a bicycle

bell grows in volume to apprise

the congregants, who can be fickle,

of one who has arrived to tell

rumors about the Ashton place,

where long years back, a skeletal

visitor with a cello case

turned up, was seen, and seen no more.

“Think nothing of it? Think again.

“This out-of-towner, just before

she disappears, solicits men—

three of them—at the Bar & Grill.

She brings them back to Ashton’s hole.

They aren’t seen again, until

one day the case is found. Out roll

three severed heads….” And more besides.

Clichés abound: a woman scorned

is not the worst, by half. As brides

in widow’s weeds, as girls adorned

in frilly night-dresses, as hags

sobbing in hospital gowns,

they roam their ruins, or so brags

a voice that doubles as the town’s—

patrician and authoritative:

A boy of 12 who walks a Schwinn

ahead of them, dispensing native

chestnuts about eternal sin.

Sunil Iyengar lives outside Washington, D.C. and writes poems and book reviews. He is the author of a poetry chapbook, A Call from the Shallows (Finishing Line Press) and editor of The Colosseum Book of Contemporary Narrative Verse (Franciscan University Press).

J. M. Jordan

Incident on the St. John's River

I.

Flat black water, sparrow-spangled sky.

The surface of the river flames with gold

around you like a flaring sheet of tinfoil

as the outboard’s mighty gurgle levels out

into a wet sustained hypnotic hum.

You lean way back and slice the wooden skis

across the wide increasing wake, carving

a sheet of spray. A bright refreshing mist

lifts from the little white caps as they curl

and fade out toward the sawgrass on the banks.

This is the moment you are here for, this

pure summer, golden, open wide and humming

up through the tow-rope to your magic hands,

the river thrumming hard beneath your feet,

the blazing windrush drumming in your ears,

and blaring from the radio on the boat,

above the crackle of the beat-up speakers,

that timeless guitar solo, silver notes

ascending free and skyward like a bird now

from a dense morass of swampy power chords.

You are the racing rakish cavalier,

hell-bent and full-tilt over open fields,

the stuntman going hard at break-neck speed

to hit the ramp and jump the swollen creek,

the dashing highwayman, the moonshine runner.

You are the hero, wild, victorious,

parading through a roaring hometown chorus,

through corridors of sharp defiant flags

and bright bikini girls that smile and wave

from lounge chairs on the lawns of grand estates.

II.

Mile after shining mile blurs by until

you’re further up and further in, way back

on unfamiliar water near the swamps.

The river narrows, and the cypress trees

lean out and spill their shade across the water.

The little docks that dot the poorer stretches

like outposts disappear, and great black shapes

turn here and there up in the yellow reeds.

A sudden mass of thunderheads rolls up

across the sun. The river-world goes grey.

Your cousin lifts a beer above his head

and waves it in a circle like a halo

then turns the wheel to nose the boat back home.

You drift out wide to keep the tow-rope taut

as minnows scatter in the sandy shallows.

And there you spy a little cave-like cove,

a world within a world, a dark enclosure

all overhung with oaks and twisted cypress,

a setting like a school kid’s diorama

to illustrate some eerie backwoods tale.

Grey wisps of moss frame the murky inlet,

and in the dark you see thick ropes of kudzu

tendrilling down around the empty windows

and rotten skull-like frame of an old wreck,

a stove-in houseboat jammed up on the bank.

Aslant and weathered ghostly long ago,

it rests like it had drifted heedlessly

from out the cool and placid middle channel,

had strayed from its own dream too close, too close

to dark and native trouble on the banks.

It ain’t like danger’s ever far away

here in this world of hidden moccasin nests,

of twelve-foot gators, armored saw-tooth gar,

of gas cans, guns and whiskey-primed audacity.

But still a different tremor makes your knees

go weak, a fear that brings to mind old stories

of inbred swamp folk, ghosts of ragged slaves

absconded, remnant bands of painted warriors

or fever-struck conquistadors who found

no gold, no magic fountain in the end.

Then just before your cousin straightens out

and points the bobbing prow back down the river,

a blank white face appears, a featureless visage

framed in a skewed black window of the wreck.

It floats there in its little pool of darkness

a moment, like a ragged moon, a portent,

then disappears. At once intent and heedless,

you stare transfixed. Your right ski clips a log

half-hidden in the shallows, and your knees

go shaky as the sky wheels overhead.

Your cousin laughs and spits and pumps a fist

then opens up the throttle like a shotgun.

Your sunburnt knuckles whiten on the handle,

your legs now stiff, steadied by the fear.

You shake the vision from your head. A trick

of light? A drop of water in the eye?

The ghostly wreck in speeding seconds now

drops out of sight, the small dark alcove just

a patch of shadow in the distant tree line,

receding down the river, and away.

A light rain starts to fall. Your sunburnt skin

begins to chill and prickle trekking homeward.

The flags are still, the tan bikini girls

have disappeared into their brooding manors.

There are more things in heaven and earth, indeed,

than even Florida sunlight can dispel

from the depths below, above, around us. So

you keep it in the middle of the channel,

where the water’s smooth, being careful you

don’t cross your skis, don’t let the rope go slack.

Back on your papa’s dock you crack a beer

and nod and smile and don’t say much at all.

J. M. Jordan is a Georgia native and a resident of the Old Dominion. His work has appeared in Arion, Gray’s Sporting Journal, Louisiana Literature, Modern Age, Southern Poetry Review, and elsewhere.

Mattie Quesenberry Smith

Autumn, Without Her Healing Hands

Leaves crack the silence,

Whip, wind-torn in snags of branches.

Black grackles dive in quick arcs

To balance, wedge-tailed, on stronger limbs.

Leaves have been falling here, purple-veined

And drained like the hands of some old, old widow

Wrapped around her rocking chair arms.

Crisp air rushes through wisps of her hair,

Her chair, now creaking, now still.

Some leaves are full-blown purple from

Blood’s final rush through weakened

And collapsing veins. We are not dismayed:

Days growing shorter will lengthen again.

The leaves kicked off bits of budding green

Before they twisted and slipped onto unwinding spirals.

But when this widow dies, no one takes her place.

No one to heat up stinking salves

And pass on the wisdom in wives’ tales.

We walk out Wind Rock Ridge to her lane,

Jump onto her oak porch,

Run through the door, and

Catch her in the kitchen

Where she should have been baking.

Her house, bleak-boarded and bare,

Withstands a scrub oak thicket.

Withered hands, wrapped in a purple pallor,

Shift in sunlight and dapple the grass,

And the split rail fence leans this way and that

Like a skinny, broken back.

As the Commonwealth of Virginia’s Poet Laureate 2024-2026, Mattie Quesenberry Smith was awarded an Academy of American Poets Laureate Fellowship for her civic project “Perseverance and Resilience: Serving Veterans through Poetry.” Smith is a first-year writing and rhetoric instructor at Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, VA, where she lives at the foot of House Mountain with her husband and family.

Helena Feder

Camouflaged

If this were real life, I would soon come eye to eye

with ones larger than mine on the back of a black

insect, unseeing neon circles painted by nature

to deter predators like those office experiments

enforcing honesty with a circumferenced pupil taped

above a coffee collection jar. It says something like God

is always watching. Eye teeth. Conversely, camouflage

hides us from others, a work of deception designed

to blend in such a way that we forget even ourselves

as in those dreams I’m a wide winged thing circling

this fat green fig on which a long arthropod feeds, my eyes

keener judging I can take the fruit and beast at once,

that these circles do not see me, that this neon is no poison,

that the uncanny is human, that no one watches above.

Helena Feder has published poems, essays, and interviews in venues including North American Review, The Georgia Review, Radical Philosophy, Orion, ISLE, ASAP/Journal, Terrain.org, The Writer's Chronicle, Another Chicago Magazine, After the Art, Guernica, Green Letters, Tikkun, Western American Literature, and Critical Read. Helena is Editor of Tar River Poetry and Professor of Environmental Humanities at ECU.

John Poch

Lunatic

—they who make reason subject to desire

Inferno 5.39

Where was it we first heard that moths collide

with a lamp because they fancy it’s the moon?

I wanted to believe, for who wouldn’t side

with a fragile thing that hurts itself so soon

after emerging into life, that lies

in wait for night because of sun-blind truth.

She alters lust to just, perchance, and flies

romantically to blaze: perforce, forsooth!

The moth, no butterfly, no Beatrice,

but shades of wild Francesca to strange flesh gone,

in blackness of darkness she swerves to sacrifice

much hotter than she thought, dumb, blind as bone,

then falls like a petal on a doorstep. Pity,

but no. I pick her up, and her wings turn

to dust, a worthless sensual sparkle. Pretty

vicious, a soul of ash, she loved to burn.

John Poch's work has been published in Paris Review, Poetry, The TLS, and many other magazines. His eighth book of poems, The Future of Love, is forthcoming with Slant Books next year.

Jared Carter

November

The doorways now entirely

grisaille, at dusk,

The Duomo’s shadow could not be

more pale, the husk

Of crowds that flow along the bridge

more tenuous—

Dissolving now, the city’s ridge

of towers must

Give way to echoes—cobbled streets

and stones, and all

That mattered once, no more discrete

than shades that call.

Jared Carter’s most recent book of poems,

The Land Itself, is from Monongahela Books in West Virginia. He lives in Indiana.