Interviews

Jane Satterfield and Lesley Wheeler

Poetic Ecologies: A Conversation

Jane Satterfield: Lesley, congratulations on

Mycocosmic—it’s a stellar collection of mourning and transformation that explores the wild and wonderful world of fungi. At the same time, the poems pay witness to time’s passage, ecological collapse, and—to borrow a phrase from mycologist Merlin Sheldrake—the entanglements of our lives.

I’m struck by the way your books—poetry and prose—share a specific constellation of energies and yet, in terms of structure and approach, they’re consistently innovative and surprising. One of the first poems of yours I read was “The Calderstones,” a finely honed sonnet crown referencing a ruined megalithic monument in your mother’s native Liverpool. It’s a poem that moves straight past your basic bit of “stone bothering” to build a powerful meditation on inheritance and the need to break through the silences of the past.

But back to the present book with that visually striking cover of a levitating mushroom. The title’s a neologism of your invention, right? Is there a story behind your choice of artwork?

Lesley Wheeler: Thank you for the kind words about Mycocosmic and for the phrase “stone bothering”—that’s new to me and brilliant. I love how it implies consciousness in ancient megaliths. It also led me to the “Ancient Stone Bothering” Facebook page. Who knew?

Yes, “mycocosmic” is a neologism, which means that people can pronounce it however they like. (I’ve been noticing how many different pronunciations exist of “fungi” and related terms, contributing to mycology’s lovely weirdness.) I wanted a word suggesting the book’s mycelial underpinning, but “mycoverse” and “mycotopia,” for example, already exists in book, podcast, and brand names. One advantage of “-cosmic” is its woo-woo associations, since the book contains so many poems about divination. The second half of my invented word also implies other worlds and afterlives. I’d noticed how most of my poetry book titles evoke place in an uncanny or psychological way: Heathen, Heterotopia, Radioland, The State She’s In. Spacetime might be my flood subject, to use Emily Dickinson’s phrase.

As far as the cover, lots of botanical images of fungi are muted and brown, and I like color, so I went looking for photography and art with a vibrant take on either mushrooms or mycelium. Finally I asked a talented colleague, Emma Steinkraus—a mycophiliac who has painted foraging scenes—if she knew of anything that might work. She pointed me to the “Radiant Void” series by Pearl Cowan. I adore how these watercolors are beautiful, botanical, and spiritual all at once.

Speaking of which, your sentence about paying “witness to time’s passage, ecological collapse, and…the entanglements of our lives” describes your collection The Badass Brontës equally as well as

Mycocosmic. Addressing temporality first: your erudite, moving, and yet somehow playful collection (Emily’s tattoos!) rhymes the Brontës’ time with our own, especially through pandemic and toxic technologies, documenting those resemblances as well as the complexities of their literary reception over the years. You’re part of that reception, through this book, but your poems and epigraphs reference responses by biographers, painters, poets, and so many more, expanding the Brontëverse.

I knew long before this book saw print that you were a passionate reader. At what point did you realize that your specific fascination with the Brontës would become a collection? How did your title and cover come into focus? I’m thinking about the adjective “badass” in tension with that distinctively literary name, as well as those ghostly feet in the grass. The translucent hem in the cover art puts me in mind of your poem “Emily’s Apocrypha,” the tease of a history that’s partly visible, partly lost.

JS: “Stone bothering” is a fantastic term—I agree. And I love the lore, the petrification myths, surrounding them, that the stones are actually people. At some sites, they’re said to slip from the circle once a year and head to nearby streams, or they’re maidens who were punished for dancing. Visit a stone circle and you’re halfway to an ubi sunt. Megaliths do feel alive with the imprint of deep time, plus they’re peppered with forest-like blooms of lichen—whole ecosystems are clinging there. With the Brontës, I followed a winding track through a long fascination with their lives and works. They appeared elsewhere in my work, then gradually took over. As with many books, you write a few poems, then a few more poems, and then you’ve gone beyond a sequence or a chapbook into a kind of fever dream.

Apocalypse Mix, my previous book, centered on war and the ways it infiltrates our lives and language; it was a deep dive into family history. By the time it came out, in 2017, I was already writing biographical poems about Emily, which felt risky and possibly retro, maybe too self-consciously literary.

But the more I spent time with these sisters the more I found “rhymes” with our own era. The wanton environmental destruction in the name of progress that’s about profit for some, poverty for others, was central. The way the Brontës adhered to or rebelled against gender expectations of their time was another element—working as ill-paid teachers and governesses, or, in Emily’s case, deciding she’d rather stay home with her father and take on domestic duties, if it meant she could live mostly in her own head.

My original title centered on fire and frost, motifs that recur in Emily’s poems, but it didn’t really capture the sisters’ gritty determination to speak their minds in print—which required some serious badassery. In the title poem, I imagined the sisters as contemporary superheroes striding across the moor. The cover image you described so well is called “Sinking In.” It’s a painting by artist and illustrator Kelly Louise Judd, whose work has a playful neo-Victorian quality—elemental, folkloric, filled with woodland creatures. All very Emily.

Your own book, Mycocosmic, is also centered on ecology—specifically the lore around mushrooms, which are, of course, the fruiting body of decay, but bring to mind associations of sustenance and magic rituals, decay and transformation. You dive into complex underworlds of sex, motherhood, mortality, and the fraught spaces of submerged memory. Did the book start out intentionally, like a concept album? Or did poems emerge in a less consciously strategized way?

LW: Heterotopia, exploring my mother’s childhood in Liverpool during World War Two, was a concept album. Mycocosmic developed differently. On the one hand, I’d become a student of mycelium, the underground organism from which mushrooms sprout. That preoccupation was emerging in my poems. Then, in late winter 2021, my mother’s lymphoma recurred, and she died a few weeks later. That crisis loosed a spate of poems, first about her death, then about the submerged memories you mention. My mother always read my books. I hadn’t realized how much I was holding back with her in mind, especially material about childhood violence, mental health, and sexuality.

In 2023 I knew I had more than enough new work for a collection, but I had no clue how those pieces fit together. Then it hit me that fungus metabolizes death, breaking down the toughest cell walls to help make new soil. I had been writing toward transformation for a while, the midlife transitions of menopause and empty nests and dying parents, and mycelium could be a muse for the process.

To what extent did your rereading of the Brontës feel like a medium for or parallel to other questions you wanted to address? There’s so much here about ecological crisis.

JS: Great question. I think mourning and lament are necessary aspects of our work in the Anthropocene and I was lucky to have a trinity of muses for this strand. The Brontës lived in an unsanitary, overcrowded town and were familiar with disease, particularly TB which took a heavy toll on the family (only Charlotte outlived her siblings). But the sisters’ love of the larger-than-human world is evident—their work is so rich in terms of its naturalistic description, so absolutely jam-packed with word pictures, they practically provide a baseline for tracking climate change.

I’d like to mention Poetry’s Possible Worlds, your recent essay collection, a hybrid memoir that fuses creative nonfiction with literary analysis. I see aspects of this hybridization in “Underpoem,” the cento (or lyric essay) that runs beneath Mycocosmic’s individual poems, a connective thread that mirrors the understory of a forest. I’m curious how this piece came to be and where it fit into your drafting process?

LW: Thanks for revealing that echo between my books—you’re right that I’m more and more attracted to genre-crossing. “Underpoem [Fire Fungus]” was the last poem I wrote for the book, and it feels hybrid in method as well as subject matter to me, too. I had done so much research, and in the underpoem I could finally be scholarly and discursive about it, documenting some of the sources that inspired me even as I made certain associative, emotional connections explicit. The “fire fungus” element calls back to an early vision, too. A Tarot reader told me at a key moment that “good things come to you through fire,” and I had a dream about a stone goddess telling me my next book should be about dragons, so transformation through fire was a motif from the start. I had become uneasy, though, about my working title Good Things Come Through Fire. The Anthropocene has brought frequent, devastating wildfires, and I didn’t want to sound cavalier about that, although fire does play a crucial role in the renewal of many ecosystems.

There’s plenty of fire in the Brontë novels (and in their lives), as well as in your poems about them—as well as thunder, letters, and real and imagined landscapes. Is there a motif or metaphor that became especially salient to you as your research deepened, or as you considered your own relationship to these figures? I’m also really interested in the role of research in your poetry life.

JS: I thought about weather a lot, for sure, not least because of the word wuthering that Emily uses, a Northern English word, for the sound of the roaring currents on the moor. She might have been a keen meteorologist: in the midst of December, she wrote one of her most ecstatic nature poems, “High Waving Heather,” which is a stunning response to seeing the moors in full summer dress—the vibrant purple heather withstanding the storms, the wind itself “Roaring like thunder, like soft music sighing.” Like the Romantics, the Brontës are as attentive to inner weather as to the atmospherics of place.

I find research brews poetry. With this book, I read a lot of biographies, a lot of critical and other reading for social/political context. But I also followed random trails. When a poem’s getting stuck, I look things up—a process that led to “Self-Portrait as Thunder and Lightning” where curiosity about Victorian-era fashion led to the fact that Emily actually wore a dress with lightning bolts—recent screen Emilys Chloe Pirrie (To Walk Invisible) and Emma Mackey (Emily) wear colorful reinventions, but you can see a replica of the actual dress in the Brontë Parsonage Museum.

Archival research played into the book as well. “Emily Inked” was inspired by spending time with manuscript pages held in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library. Her curious doodles made me think she’d have been enchanted by tattoos. So one minute you’re doing your homework, then the investigations reveal unexpected gifts. I love site visits as well. The spectral imprint of a place lodges in your brain, this book being a prime example of how that happens.

Your own passion for research is evident in Mycocosmic. Some poems find ways to incorporate a scientific or environmental strand into more personal narratives, while others reflect a more documentary-historical focus. “Harrowing” is a chilling look at the isolation and privations brought about by a global pandemic. And “You Know Where the Smithy Stood by the Clinkers” incorporates conversations with colleagues in other disciplines who share insights about our nation’s darker legacies, including the role of enslaved labor in your university’s history. I wondered if your archival work precedes the poems or vice versa? Do you see the process of writing the more confessional poems as challenging as those poems whose subjects may be only tangentially related to autobiography? Has your scholarly training in Modernist Poetics pushed you toward (or against) one mode or the other?

LW: Sometimes I set out to research a subject before I write about it, but chance finds can send you in unexpected directions. A couple of summers ago I began work toward a lyric essay on H.D.’s use of Tarot by visiting Yale’s Beinecke Library. I ended up spending a lot of time with what most would consider a minor exchange of letters between H.D. and an old friend who led a conventional life in suburban New Jersey, very near where I grew up. You never know what random discovery will ignite an idea. The same goes for a lecture or reading you attend, a reference in an article you read, a mural you spot—anything can send you down a rabbit hole into a refreshed world.

Research has rigors, but I find conducting it easier than writing about high-stakes personal material. Vulnerability, a sense that an artist is willing to look bad or expose a tender spot, makes art moving and urgent. I’m stunned in the best way when I encounter it in poetry by others, but it’s hard to face your own hurt and shame.

Modernism definitely inspires me with its experimental textures and intellectual breadth. But Confessional-era poetry, and later work with a similar take-no-prisoners fierceness, inspires me too. For a long time, trained in my PhD program that first-person poetry conveys a naïve understanding of identity, I resisted autobiographical writing. Now I suspect that prejudice undercut my early poetry’s power. I mean, look at Plath, one of our mutual favorite poets. Her poetic “I” could not be more multiple, unstable, and crafty. Verse can be confessional and immensely complex.

What I do find challenging about research-driven poetry—and poetry of political and ecological witness—is the transmutation of information and argument into sensory detail and sonically dense lines. In “Harrowing” and “You Know Where the Smithy Stood by the Clinkers,” you’ve pinpointed two poems I revised many, many times, trying to boil polemic down to poetry. You’re so good at this branch of witchcraft. “Letter to Emily Brontë,” for example, is jam-packed with facts about her time, our time, Covid protocols, animal extinctions, Brontë family lore, and more—while maintaining lyric intensity. Do you have composition strategies or processes that help you achieve this?

JS: Thanks for your kind words about that poem—it’s one of my favorites. You’re right: revision is key—often it’s about voice and scale. Sometimes more than a brushstroke of research will sink a poem. I love epistolary poems. Letters give you permission to shift rapidly between worlds and registers.

Earlier you mentioned Plath, but I also think about Bishop here, in terms of subtle or surprising shifts in voice and tone that are consistent with the chattiness of letters. Your work is filled with rich description of the natural world and infused with a deep ecological vision. Animals—birds and other creatures—appear with striking frequency as beings in their right, and often as ambassadors or messengers. Do you see your poems as a part of an otherworldly tradition that incorporates the spectral and/or the uncanny?

LW: Totally. For me, reality shimmers. Sometimes you can glimpse other realities behind it. I’ve many times felt that the sudden appearance of a bird, animal, or insect delivered a message. An epiphany behind Mycocosmic was a moment I stood barefoot in my yard next to an old maple tree. My quarter acre had once contained two other maples of about the same age. I suddenly wondered if they had been communicating with each other, sending nutrients and warnings back and forth through mycelial networks. Then I wondered if the surviving tree and the mycelium beneath us were aware of me, as I had just become aware of their secret lives. Were they calling me to notice them, even? I felt myself as one node in a longstanding ecosystem. It was numinous.

Surely you feel similarly, as did Emily Brontë, I gather, especially about animals.

JS: Absolutely! When I started writing about Emily, I remembered that she rescued a hawk. Living in a suburban neighborhood rather than a village that backed onto the moors, I saw foxes and the occasional deer materializing in the yards and alleys. It felt magical, but was part of a larger story of habitat loss and resilience. So the book is a bit of an urban bestiary. And Emily and Anne kept a quite menagerie—beloved dogs and some rescued birds—an endearing quality.

With Mycocosmic, you’ve joined the ranks of poets who engage in divinatory practices—Yeats with automatic writing, Plath with tarot, Merrill with the Ouija, Harjo with ritual invocations, and others I’m not thinking of. What drew you to explore tarot and the tradition of spell casting—is it a source of inspiration, healing, or something else?

LW: Like you, I love intricate sonic patterning in poetry, an oral or musical quality that tends to characterize spells and prayers, too. Plus, in looking to transform myself—and thinking about how transmutation happens in the other-than-human world—I was wondering what role language can play in metamorphosis. Petitions to nature and to supernatural beings have long been a way to seek change.

I’m using abstract language, though, and it’s more than that. As I say in “Flammable Almanac,” “I picked up the cards as a kind of game.” Tarot was a pandemic hobby, a new way to play around, but at another level I was desperate. The world had shut down and I was longing to imagine life after Covid (ha!). I’m no expert in Tarot or any other kind of divination, but sometimes when I lay out a spread, I catch glimpses of understanding. It’s rewarding but also unsettling; inspiring and healing but, for me, a font of confusion as well.

You and I were once on a conference panel together about poems as prayers, spells, charms, and curses. I don’t remember what poem you read—was it one of these? There are certainly supernatural threads in The Badass Brontës, in your séance poem for example, and of course there are in their novels, too. Jane Eyre has been my favorite novel since the age of nine in part because of its gothic elements. Where is your thinking, these days, about poetry as spellcasting?

JS: Spells, charm, and prayer poems carry the weight of ritual and tradition for sure. They feel endlessly resonant, especially in dark times. Not long after that conference we all swerved into lockdowns, but our panel conversations stayed close in mind. I actually read “Malediction,” one of a pair of defixiones (curse tablets) from Apocalypse Mix, where I’m thinking about the impulse behind malefic requests to the gods. But in “Spellcasters,” the Brontë sisters are speaking for weird sisters everywhere, climbing precipices and reciting Prospero-like charms to “roll back the besmirching smoke / that the ancient forest might rise again” and to “summon a sisterhood of destiny.”

From traditional received forms like the sonnet and villanelle to the gigan and golden shovel and more, Mycocosmic is form-rich. Do you see formal experimentation as an essential part of your poetics? Do forms open doors in terms of subject matter or tonal variety?

LW: To so many of these insightful questions, I’m answering yes, yes, yes. Reading about a form that’s new to me, such as the gigan (invented by Ruth Ellen Kocher) or LaCharta (from Laura Lamarca), gets me thinking about what kind of material might be amplified or complicated by it. Form is generative. The underpoem structure that came to me in a brainstorm seemed to necessitate a discursive voice. “Rhapsodomantic” wanted cryptic little prose blurbs like those in Tarot guides. I do keep returning to free verse as well, because sometimes I need to relearn what strangeness can happen when you play tennis without a net.

The Badass Brontës encompasses a wild range of forms and tones, too: your book contains a gigan plus triolets and a cento and prose poetry and so much more. I’d be curious to hear your answer to the same form questions, and also whether there’s a mode that feels particularly congenial to you. I notice I fall into triple meters often, even when I’m trying for iambs in a sonnet.

I also have one more question, raised by your poem about the internet quiz, “Which Brontë Sister Are You?” Your poem gives three answers in the second person, but aren’t you Emily, the sister at the heart of this project? (I’m Charlotte, duh.)

JS: It sounds like we both found that established forms really open up tonal variety and become solutions to tricky narrative problems. The trio of triolets in the quiz form was a quick way of giving thumbnail bios of the sisters in a way that revealed why they still hold the attention of readers. Villanelles are dynamic yet constrained—a perfect space to pay tribute to The Most Wuthering Heights Day Ever dance celebrations that recreate Kate Bush’s 1978 video. Like Charlotte, I have my ambitions; like Anne I’m sometimes working quietly, tuning out my inner weather. Most days, yes, I am Emily, walking out into whatever open space I can find or create.

Walking, I know, is also part of your own literary practice, so my last question is about mushrooms in the wild. Have you ventured into foraging or found any culinary tips to share?

LW: I took a foraging class and have been trying to get into the woods as often as possible, eyes peeled, but embodiment gets in the way: I’ve been battling sciatica all year. I’ve been nibbling wild stuff all my life, starting with onion grass in the backyard where I played “orphans,” a game inspired by Jane Eyre. (I just looked up “onion grass,” and it’s also called “crow garlic”—nice.) When I’ve got specimens I’m sure are safe, frying in butter will be my first go-to, but I do love a wild mushroom risotto made with grated pecorino and broth from dried porcini. I also hear “crab cakes” with lion’s mane mushrooms are pretty fab.

JS: Those dishes sound amazing, Lesley. Thanks for this glimpse into world of wild stuff that is Mycocosmic’s origin.

Jane Satterfield’s recent books are The Badass Brontës and Apocalypse Mix. Luminous Crown, selected by Oliver de la Paz for Word Work’s Tenth Gate Poetry Prize, will appear in 2026.

Lesley Wheeler’s sixth poetry collection is

Mycocosmic (Tupelo Press, 2025). Her other books include

Poetry’s Possible Worlds and the novel

Unbecoming. Recent poems and essays appear in

Poetry, Best American Poetry 2025, Poetry Daily, and

Poets & Writers. Poetry Editor of

Shenandoah, she lives in Virginia.

Jason Guriel

"Stubbornness is essential": An Interview with Daniel Cowper

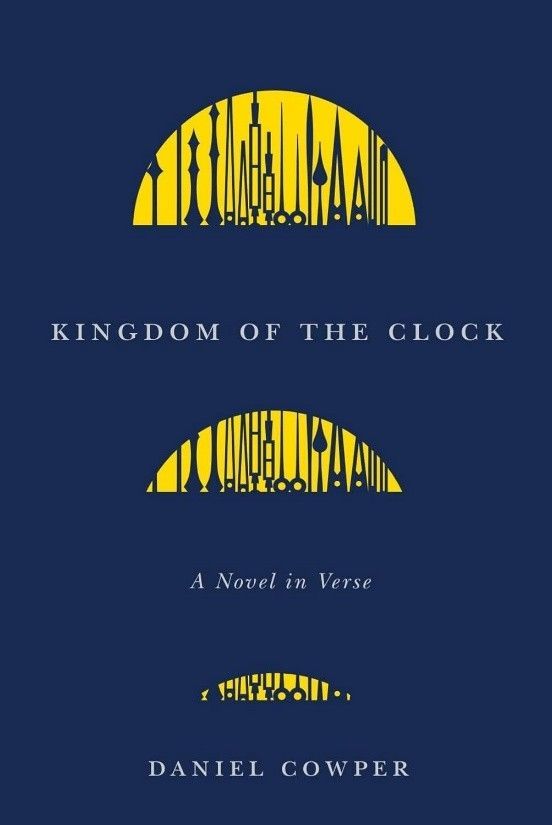

Earlier this year, Daniel Cowper landed on the Island of Misfit Verse Novelists with aplomb. His excellent Kingdom of the Clock (McGill-Queen’s UP 2025), a novel in couplets, takes place in an unnamed city that contains twenty-first-century multitudes: an artist-cum-barista, a gambling addict whose wife tracks him by way of app, a con artist armed with a pitch deck, and more. The couplets are blank, and the characters, convincing; Cowper has a way with details and dialogue that earns the reader’s trust.

And he has a way with words that earns the poet’s; his writing is “often envy-inducing,” an adjective I use in the blurb I was happy to compose for Kingdom of the Clock. (Us verse novelists have to stick together, right?)

We talk about all of this, and a lot more, in the interview below, including the limitations of lyric poems, what it takes to go long in verse, how to kill an opera, a life-changing William Logan poem, an anxiety-inducing P.T. Anderson picture, why you should give your character a pipe, and the intersection between poetry and spreadsheet.

—Jason Guriel

Jason Guriel: Why a verse novel? I mean, I know why I dabble in the form, but it takes a lot of work to pull off a book like Kingdom of the Clock.

Daniel Cowper: I started working on this book just after deciding to chuck urban life and move back to the rural island where I grew up. I wanted to write a love letter to the idea of the city; and I thought I had learned something about what makes a city tick that would be worth sharing. I didn’t set out to write a verse novel at all—the poem started as a long flow of description, but I figured if I wanted to describe the city properly, I had to write about the people who live there, their struggles, and how they get through the day.

Wanting to do justice to those characters and their problems forced me into a novelistic approach: the central characters and their narratives overwhelmed the descriptive elements of the poem, so that, eventually, I had to admit to myself that I was writing a verse novel.

JG: So is it fair to say you find the mindset required to write a lyric poem differs from the mindset required to mint lots and lots (and lots) of lines in service of a story?

DC: From my perspective, the critical difference between approaching a lyric poem and a narrative poem is openness to failure or (as you might say) pigheadedness. Not finishing poems is an important part of the lyric practice, so you can avoid either battering yourself against them or accepting their mediocrity.

A poet can fail to pull off a lyric poem because of problems with the poem, problems with the poet, or problems which are entirely mysterious. When that happens, the poem can be set aside; but it’s often better to loot the draft for parts and forget it. In my early 20s, for example, I wrote a poetry sequence about Cleopatra, heavily influenced by William Logan poetry sequences like “Punchinello in Chains.” I worked on the Cleopatra poems for a while, then walked away and never looked back.

Narrative poetry, on the other hand, requires commitment. When you work on a big enough scale, you set out knowing that you won’t have all the resources you’ll need to accomplish the goal. You know you’ll need to do research, develop new skills and tools, and write and rewrite, in order to complete the work. You can cut passages that aren’t working or aren’t contributing to the whole, but you can’t give up. Stubbornness is essential.

JG: “Stubbornness is essential”—I love that, and I agree. When talking about my own verse novels, I used to say that there was a certain point where the draft had become too big to give up on. It had become a small moon with its own unavoidable gravity.

Tell me more about “commitment.” How did you stay committed? I used to wake early, before the rest of the house was up, to bang out couplets. What did your practice or process look like?

DC: Working on something the size of a verse novel forced me to be more proactive with my writing than I used to be: I portioned off writing time at the start of workdays and going into the evenings knowing I’d write after everyone else had gone to sleep. My wife and I are raising two small Visigoths, and their barbarisms would have my wife asleep by 9pm—leaving me able to work after that for three or four hours.

That schedule let me work in the times of day I feel most creatively energized (breakfast to lunch, late at night), while leaving the bulk of the “work day” to attend to tasks that make ends meet and get the chores done.

In addition, I pride myself on getting little bits of writing done here and there, in the cracks of the day. That was something I got a lot of practice with while working downtown, and that habit of flexibility is still very valuable now that I parent and work from home. But there’s no getting around the requirement for stamina: as T.S. Eliot said, anyone who aspires to literary work must do the work of two or starve.

JG: Writing in the “cracks of the day” (nice line) is essential. Who are your influences?

DC: Well, William Logan was the first contemporary poet who proved to me the English language was still latent with magic. It sounds pretentious, but when I was young I genuinely suspected that English, in its present condition, was not a good medium for poetry. A friend showed me Logan’s poem “The Saint and the Crab” in The New Yorker, and my doubts were dispelled.

Logan got me through university; after I started working in an office, Joachim du Bellay kept me going. Over lunch breaks, I’d translate sonnets from his Regrets. I loved his direct tone and identified with how he felt about having to direct much of his energy into a demanding day job. Those are great poems to live with.

I’d also be remiss not to mention the video essay series Every Frame A Painting, by Tony Zhou and Taylor Ramos. Tony and Taylor discuss filmmaking, but much of what they say about images, scenes, narration, and character was very inspiring to me when I was writing Kingdom of the Clock. Thanks to them, I have come to think that, in a shared need for succinctness, vividness, and emotional structure, cinema and narrative poetry have much in common.

It’s difficult to disentangle what’s influenced me as a reader from what’s influenced me as a poet, and I’ve had too many formative enthusiasms to name them all. Those are three that I think would be rude not to mention.

JG: Reading your book, I thought about P.T. Anderson’s Magnolia—a picture that unspools across a single day. And then I thought about Ulysses, Mrs Dalloway, and other classics of day-in-the-life lit. How did you arrive at the book’s structure, the temporal conceit—the “clock” in the title? And did you have any predecessors in mind?

DC: Even when I first conceived of the poem as a description of a city, I intended its action to fill a twenty-four-hour period, thinking it was essential to comply with how the sequence of hours defines urban life. In the countryside other temporal cycles play a big role in people’s lives: the weeks, seasons, moons, and even tides are all very important. On my island, the ferry schedule, in a very real sense, takes the place of the clock. If the ferry schedule shifts, as it does once in a while, even the hours when a school day begins and ends are shifted. In cities, the clock itself reigns unrivalled.

In other words, I felt bound by that temporal conceit, which is built into some of the other structural details. Not only is there a canto for each hour, but the closing line of each hour is echoed in the opening line of the next, as if they were gears whose teeth fit together.

When I had made the central decision to let the city express itself through the dramas of individual citizens, the temporal unity I had begun building on served a secondary function of offsetting the complexity of the poem’s action.

When I was writing Kingdom of the Clock, I actively tried to avoid thinking of any models or predecessors, except, to some extent, so far as I had to monitor myself to avoid falling into inadvertent imitation. I have since thought with a little anxiousness about Magnolia, which (if I recall correctly, not having seen it since it came out) is also concerned with affirming the value of individual humanity. Magnolia’s famous climax, with frogs raining from the sky, also seems to me to gesture towards a spiritual reality that in Kingdom of the Clock is represented by the amorphous spirits “cycling on solar winds.”

JG: T.S. Eliot says somewhere that “the business of the poet was to make poetry out of the unexplored resources of the unpoetical.” I’ve always liked that line, and when I read Kingdom of the Clock, I feel like I’m seeing a poet making poetry out of the unpoetical. For example, there’s the scene where “Connor’s guiding // prospective investors through his pitch deck.” Now, I’ve developed pitch decks for my day job, but I don’t think I’ve seen pitch decks in poetry before.

Maybe this is a leading question, but do you see narrative verse as opening up opportunities for poets to plumb the unpoetical? What does narrative verse allow, subject-wise, that lyric poetry doesn’t necessarily encourage? Are lyric poems resistant to pitch decks?

DC: I think so. A lyric can only assume a limited amount of context on the part of a reader — it can be difficult to introduce things that aren’t familiar to most readers. As a result, lyric poetry can often be doubly limited: limited by the poet’s own experience and limited by the poet’s expectations about what readers will be able to relate to.

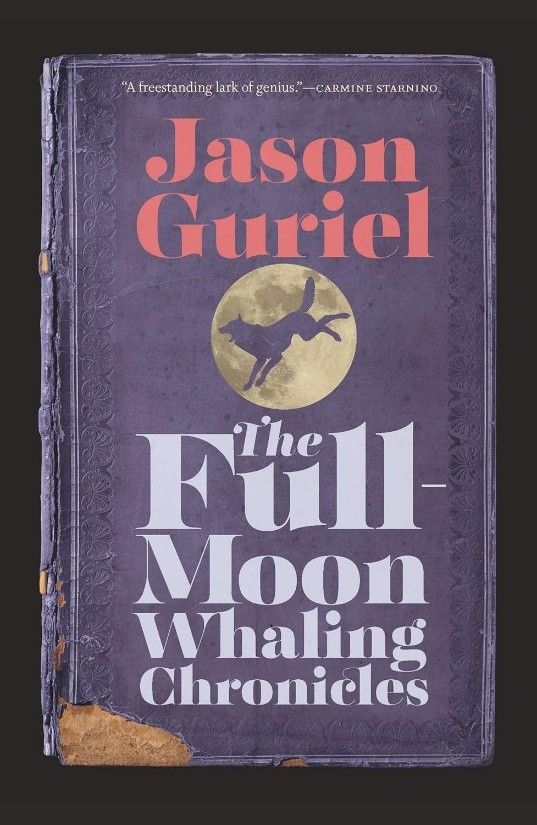

Within a larger narrative, the reader can be given enough context to relate to nearly anything with understanding. If you have characters and plot, you have a framework within which all manner of things can be established and set up. In The Full-Moon Whaling Chronicles, you make the description of future technology not only engrossing but entertaining — while as someone or other said, it’s a challenge even to get a microwave oven into a lyric poem without it feeling forced. It’s a shame, but so much of real life doesn’t fit within the constraints of a lyric poem.

Pitch decks are a great example. People put a lot of effort into pitch decks. And pitch decks move mountains of money; lives are built up and broken by pitch decks every day. Not to bring up trauma you may have experienced in your day job, but some people have multi-hour meetings about pitch decks. In

Kingdom of the Clock, I wanted to talk about real life, and pitch decks are as much a part of real life as coffee or chess, a child’s birth or a friend’s death.

JG: You’re a dab hand with alliteration and internal rhyme. There are so many micro-moments in your novel that wow me: “cared-for kids,” “steam // rising from the seams of tinfoil crimped / round salmon filets,” “To chase / the chalice of art,” “Landlords make their rounds, push slips // through mail slots whose metal flaps fall back,” “her bank // account blank,” “Armin’s canary, // singing pertly from perch to perch, / offensively alive,” “Adanac’s // overdraft is still untapped, held back / for payroll. He drains it, dreaming it’ll double // by dawn.” (Oh, and that crimped tinfoil seems to me yet more poetry extracted from the seemingly unpoetical!)

But anyway, I do have a question. I think one challenge for the verse novelist is keeping the verse vibrant even as they try to push the plot forward and amass pages. In other words, it’s easy to stockpile a lot of less-than-stunning lines. But you have a high success rate, which, I think, is what makes the book itself a success. As you were writing, were you conscious of trying to maintain a certain density of sonically rich poetry? How did you balance the novelist’s need to advance the plot or develop a character against the poet’s need to make music?

DC: I’ve seen a lot of opera, and it has convinced me that the narrative must be effective in order for the music to be heard. I’ve seen Carmen so dowdily staged that “L’amour est un oiseau rebelle” was a snooze-fest; I’ve seen Don Giovanni killed by a staging that undermined the narrative.

But when opera is musically and dramatically effective? In a good production, “La donna é mobile” makes us cry at the end of Rigoletto, and then, as we hum the tune homeward, our feet and hearts feel lighter.

That’s what I aimed for in Kingdom of the Clock: memorable verse that “sang” on its own but also intensified the interest of characters, the vividness of scenes, and emotional resonance of the narrative. That meant harmonizing what I think of as the micropoetic level (the qualities of writing that you’d also find in a lyric poem) and the macropoetic (the qualities of writing you’d also find in a prose novel).

How do you orchestrate that harmonization? For me, it was a labour-intensive process. One method was to copy out by hand the entire poem (a practice Auden recommends, on the grounds that the fingers are bored more easily than eye or ear) and to use the slow pace of pen and paper to assess whether each moment was receiving exactly the right amount of weight both poetically and dramatically. Inevitably, I added and subtracted quite a lot. I doubt there are any short cuts: if you find one, let me know.

JG: Ha, I have no shortcuts. I love that you copy things by hand. I used to do a lot of longhand writing—especially at the beginning of a project. I liked that it slowed me down.

I often reach for that other Eliot saw, “There is no method but to be very intelligent.” Comically unhelpful, but true. For me, it’s about writing good lines, one by one. “Good,” though, means a lot of things: maintaining the meter, satisfying the rhyme scheme, coming up with original but precise similes and metaphors, avoiding cliché, making sure the characters are revealing themselves through believable dialogue and interesting actions—and trying to do all of this at once!

Occasionally, I try to take a drone’s-eye view, but there’s so much to do, on a line-by-line basis, that I tend to stay pretty micro. I think my thinking is something like: if I take care of the details, the bigger picture will take care of itself. A verse novelist is someone who’s digging themselves out from under a whole heap of constraints.

Speaking of detail, you have an eye for hi-def images: the artist Viro’s “one enamelled Creuset poet,” “the padlocked // pre-fab shed” that holds a public chessboard’s pieces, “raindrops // hopping on the hood,” characters flipping “rattan chairs” onto a café’s tabletops at closing time. The world of your novel seems thought out and thoroughly textured. It seems real. Is it safe to say a commitment to realism, to the texture and grain of reality, is important to you?

DC: Kingdom of the Clock was intended to make some accurate observations about contemporary urban life, and in so doing, to make a case for what urban living does, and doesn’t do, for and to urbanites. There’s a documentary dimension to Kingdom of the Clock that I felt imposed on me a duty to avoid the concocted or unrealistic.

There are always practical reasons to write with commitment to detail. I think one aim of art, as a mimetic undertaking, is to persuade the reader of a new reality: to make it “seem real.” In pursuit of that undertaking, the vivid detail is persuasive. I used to spend a lot of time in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and I loved Ingres’ stylized portrait of the Princesse de Broglie. It is a very idealized portrait, but I have overheard remarks that it “looks just like a photograph.” It looks nothing like a photo, but I understand why they’re persuaded that it does: the level of detail is so rich and precise.

Lastly, I personally believe in writing from a posture of love. The loving eye naturally takes joy in absorbing the details of the beloved, and celebrating those details expresses that love implicitly. You know how in Graceland, Paul Simon recalls his wife telling him their marriage was over as if he’d never loved her, “as if I’d never noticed // the way she brushed her hair from her forehead.”

JG: “The vivid detail is persuasive”—yes. I’m thinking about the part in your book where Mehrdad—who’s telling friends about a grandson who’s due to arrive—“waves to ward off their congratulations.” Mehrdad goes on to explain that there’s a chance the baby won’t survive. Again, I love the alliteration (“waves to ward”), but I also love the “vivid detail,” the way we see this character in that waved arm. He’s anxious about the birth, and he’s trying to lower expectations—in a kind of stoic, stiff-upper-lip style.

That’s a small moment, but would you talk a little bit about how you create believable characters? Do they exist in your mind prior to writing—or are you writing them into existence through details like the “waved arm?”

DC: Often I start with the idea of a character that makes an interesting mistake, and try to imagine why they’d do so. If I can get my mind around why a character might do something they know is wrong, or how that same character could find redemption, usually I’ll start to automatically imagine aspects of appearance or mannerism that go with the inner self. If not, I will force myself to think about different ways the character might be individuated.

“If you don’t know what to do with a character, give him a pipe,” someone said, and that’s good advice, though it needn’t be literally a pipe. Sometimes you need an arbitrary detail for the rest of the character to coalesce around. It might be a habitual gesture, or something the character has been meaning to do but is avoiding, or some troubling memory the character is still trying to understand. Details like that have implications, and working out those implications can take you a long way.

JG: While directing the western Rio Bravo, Howard Hawks instructed Ricky Nelson—a pop star who wasn’t much of an actor—to occasionally rub the side of his nose, a little gesture that the cowboy’s character seems to coalesce around. A pipe by other means, I guess.

DC: It’s funny you mention film: in one of their Every Frame A Painting videos, Zhou and Ramos say Akira Kurosawa also liked to give each actor a tick: telling one to rub his forehead as if trying to smooth the wrinkles out, telling another to shrug his shoulders as if working out a kink.

JG: Your characters are vivid, but sometimes the general inhabitants of the book’s unnamed city (Vancouver, I assume?) congeal into a kind of mass, as if the city is a machine, and its citizens, hapless cogs. At noon, for instance:

All hierarchies

of labour cease: statisticians pause analyses

of per-user-hour spend on fremium games –

designers leave designs half-limned –

draft emails gleam unsent on a million screens

while workers on break run the seawall or read,

flip tractor tires to slog through sand

for exercise. Hungry queues watch pork sliced,

crackling diced, and salsa verde grease

both block and knife.

Passages like this reminded me of modernist poems—for instance, Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro” or Sandburg’s “Chicago.” But it’s as if you’ve installed an update and Pound’s subway riders—“petals on a wet black bough”—are now knowledge economy workers. Would you talk a little bit about the importance of the contemporary city in Kingdom of the Clock?

DC: Although I’ve spent most of my adult life in cities—Vancouver, Toronto, New York—I’ve always seen the urban environment through a stranger’s eyes, and it does seem strange to me. I grew up in quite rural circumstances: drawing our water from our creek, eating our own apples; buying eggs from one neighbour, and meat from another. Doing for ourselves and our neighbours, in the way country people do.

Contemporary cities are a bit of a paradox, to my mind: on the one hand, they are the places most shaped by human desires and human ingenuity. They hold the finest artifacts of the human spirit and offer exciting opportunities for human beings to develop and express their talents. In that sense, cities are the most “human” environments.

In another sense, a city is a very inhuman environment. Life in a modern urban environment—a stony, canyon-like landscape teeming with strangers—isn’t something that human beings are naturally fitted for. They literally drive us crazy: mental health is much worse in cities than in small towns, despite the vastly superior mental health care in cities.

The presence of myriads of other people creates the opportunities that make cities so exciting; but on a day-to-day basis, city dwellers encounter other individuals most commonly as obstructions: moving obstacles on sidewalks; taking up seats on buses and trains; driving cars that block our own, or which we have to watch out for when crossing the street; standing in front of us in queues for coffee or an elevator.

What does city life involve these days? How does a city work? What does it give its citizens, and what does it demand in return? Kingdom of the Clock is all about exploring these questions.

JG: How did you keep all the plotlines straight in your head? Did you track them in a notebook or something? Did you write any of the plotlines in one go—and then disperse them into the MS?

DC: I tried a few different techniques. I made flowcharts and spreadsheets, but because of the way the various plot threads interact, those approaches didn’t get me very far. The cells didn’t line up; the arrows tangled.

Later in the process, the main technique I followed was to periodically remove all the portions of the poem concerning a particular plot thread, and paste them into a single document so I could consider that thread as a standalone story. Thinking about whether the story was missing something, or contained lines that were either flabby or superfluous, I’d make revisions and additions, then paste them back into the main text. I did that several times for each plot line.

JG: I was actually going to ask you if you’d used a spreadsheet. What are you working on now? Are you feeling the itch to go long again?

DC: There are three projects I need to finish (or abandon in despair) before I can embark on another long poem: a prose novel; a children’s novel, which is what my wife thinks I should focus on; and a book of lyrics.

There are two ideas for long poems I’ve been doing research for and would like to get cracking on when the decks have been cleared: one a retelling of the Tom Thumb legend, and the other about the Pont St. Esprit poisoning.

For the latter, I really ought to do a lot of on-the-ground research in the south of France, and for the former—well, I’ve always wanted to see Japan, whose own versions of Tom Thumb have a remarkably rich mythos around them. If I’m tweeting from one of those two locales over a sustained period, you’ll know what I’m working on.

JG: My wife is always trying to get me to do a children’s book. Tell me about these projects.

DC: It feels like bad luck to talk about unfinished projects: these are fish on the line but not yet in the boat. But I’ll risk it.

The children’s novel is a fairy tale about a pandemic: there’s a disease everyone is frightened of, and no one understands; there are unloved children; sad women; angry men; and an escape to a fantasy world which is more comprehensible, but less forgiving than our own.

The prose novel is about the ambivalence that arises in adulthood towards a childhood home: a contemporary Brideshead Revisited of sorts.

The lyric poems I’ve been writing recently have been mainly seasonal—some have even been festive—so I’ve been putting them together into a calendar sequence. Unfortunately, I’ve made it hard on myself by wrapping those poems up in a tissue of an imaginary calendar poem (a 3rd hand translation of the completed version of Ovid’s Fasti, now lost)—fabricating those fragments is a lot of fun, but I suspect a poetry publisher would want them discarded. So there is fun, but absurdity in the labour.

Each project is “nearly” done, but there’s such a gulf between “nearly done” and “done.”

Daniel Cowper is the author of Kingdom of the Clock, a novel in verse; Grotesque Tenderness, a book of poems; and The God of Doors, which won the Frog Hollow Press Chapbook Contest. He lives on Bowen Island, and is a contributing editor to New Verse Review.

Jason Guriel’s latest book is Fan Mail: A Guide to What We Love, Loathe, and Mourn. He lives in Toronto.

Sunil Iyengar

A Conversation with Jared Carter

Sunil Iyengar: To get us started, can you say something about your family life and childhood in rural Indiana? How did those factors shape your beginnings as a poet?

Jared Carter: I was born in the Midwestern state of Indiana and still live there. Indiana today is surprisingly wired and industrialized, but, in places apart from its few large cities, much of it remains rural and conservative. It has a fascinating Civil War history, and was an important swing state during the Populist and Progressive eras.

It has produced national political figures such as Eugene Debs and Wendell Willkie, and writers and artists ranging from Ambrose Bierce and Theodore Dreiser to Cole Porter and Twyla Tharp. (For good measure, toss in Kurt Vonnegut, James Dean, Larry Bird, Michael Jackson, Joshua Bell, Little Orphan Annie, and Garfield.)

An important distinction that should be made for this interview is that I grew up not on a farm, but in a small town—the same sort of close-knit, kinship-oriented, inwardly turned community, with agricultural and artisanal roots, that can still be found almost anywhere in the world. The place of my birth wasn't exactly rural; a more precise word might be traditional.

To reimagine my early years, then, think not of someone like Wendell Berry, with a team of draft horses, out plowing the “back 40”—although such activity certainly possesses dignity, and has a continent’s history behind it. Think, instead, of Sherwood Anderson, wandering on some windy night out beyond the streetlights of some small Midwestern town.

SI: Got it. Were you read poetry as a child, or made to memorize it in school? For that matter, when you began writing poetry, who were your models?

JC: I have memorized poems, certainly, but always of my own volition. My mother read children’s poetry to me and my siblings when we were very young—James Whitcomb Riley, Robert Louis Stevenson, Eugene Fields, A. A. Milne.

My paternal grandmother preferred the Fireside Poets, Browning, Tennyson. She was born in 1878 and could remember the Blizzard of 1888. Every winter, after the first really good snow, she would get out her copy of Whittier’s Snow-Bound and read it aloud to us. (I still have that book.)

SI: Were there notable storytellers in your family? Artists? Great readers?

JC: There was a decent amount of books in the house. I first began reading Ray Bradbury after finding a paperback copy of The Martian Chronicles on my mother’s shelf of books. I discovered Ruskin—The King of the Golden River—among my grandparents’ volumes. Along with Burns.

Everybody in my family read. My father was a small-town contractor, skilled in carpentry and masonry, just as his father had been. Both of them were excellent chess-players, as my older brother would prove to be. Both of them were good with any project involving concrete. My brother and I grew up lending an occasional hand at our father’s various building sites.

SI: What kind of work did that entail?

JC: Easy things—shoveling gravel, pounding nails—but we were the boss’s sons, after all. The workmen were kind to us. It was mostly a lot of fun, and always changing. As I got older, I particularly enjoyed those times when we set off some dynamite.

Every summer there was a concrete slab or an old bridge pier that had to be taken out. When I was still relatively small, at nine or ten years, and after the holes had been drilled, if there were close quarters, my father would have me squeeze in between the old slabs to set the charge and string the wire.

After we had retreated a safe distance, he would let me twist the detonator handle. I would shout “Fire in the hole!” and everybody would duck for cover. It was a “John Wayne” sort of thing to be doing, and the envy of the neighborhood kids. (For more dynamite foolishness, see my poem “Transmigration.”)

SI: Amazing. Clearly your father gave you a lot of responsibility for your age. What was your mother like?

JC: My mother was a homemaker, a church lady, and an excellent singer, with a fine contralto voice. She made her pin money by singing for local weddings and funerals. She partnered with a pianist from her church. They were the first artists I ever knew who made money from their art—something I’ve never been very good at.

But the most significant influence of all turned out to be that of a paternal great-uncle, who went off to Paris in 1903 to study art and had a fascinating life. His name was Glen Cooper Henshaw. He died in 1946. There were several of his oils and pastels in the house where I grew up.

It took a long time for me to understand what he had achieved, but it was to be extremely important for my interest in trying to become a writer. Someone in my family had already found his way to the Belle Epoque of Rodin, Rilke, and Loie Fuller. Maybe I could do something like that.

Certain of my poems pay tribute to this great-uncle—"Configuration” for instance, in my second book, which begins, “What I first knew of a life of art / was what he touched last.” (When I was at Bread Loaf in 1981, in Howard Nemerov’s seminar, Howard was particularly taken with that poem, and told the class it reminded him of Proust.)

SI: You attended Yale. Were there faculty or students who made an impression on you when it comes to poetry and the arts?

JC: In those days Yale College had not yet become coeducational. There were no classes in grammar or remedial English. If you hadn’t already learned how to write in secondary school, you wouldn’t have been admitted in the first place.

The majority of freshmen did not show up there expecting to be taught how to write, but to be introduced to Western culture. “We are far from able to instruct you about everything of importance,” the professors said, “but we can help you practice reasoning and the examination of evidence and sources. For the rest of your life, you’ll have to decide things on your own—everything from issues of war and peace to the art and literature of your own generation. Yale can get you started.”

I was a raw youth from the provinces. It was a wonderful place to be—excellent classes, great professors. At every turn there were dazzling visiting lecturers. I got to hear Frost, MacLeish, Styron, Bellow, Mailer, Ginsberg, Corso, dozens more. What B. F. Skinner, Ayn Rand, and Herman Kahn had to say still haunts me. But what Dwight Macdonald had to say about contemporary writers was eye-opening.

I remember listening to Robert Oppenheimer, introduced by Margaret Mead. They seemed to have stepped out from the chorus of a Greek tragedy. At lunchtime in my college, Saybrook, I might suddenly find myself sitting across from Robert Penn Warren or Harold Bloom.

I also had undergraduate friends at Harvard, Columbia, and Brown, who could put me up in their dorms. This enabled me to attend lectures by people on the order of Edmund Wilson, Alfred Kazin, and Lionel Trilling. If I kept quiet, I could sit in on a seminar with someone like C. Wright Mills or John Kenneth Galbraith.

I took the train to Manhattan every chance I got, and saw plays and musicals:

Dark at the Top of the Stairs, Long Day’s Journey into Night, My Fair Lady, The Iceman Cometh. At the 92nd Street Y I heard Isak Dinesen read (I sat behind Marianne Moore). My friendship with Terrence McNally, at Columbia, who was already beginning to explore the NY theater scene, led to my meeting Edward Albee and John Steinbeck.

Another friend took me to dinner with his friend, Jason Robards, Jr., who played in both Long Day’s Journey and The Iceman Cometh. Jason brought along his father, Jason Robards, Sr., a prominent actor in the 1920s, who told me how he and Tom Mix used to get some horses together and go out in the desert near L.A., where there were all kinds of abandoned movie sets, and shoot silent-film westerns. “We never had a script,” he said. “We made it up as we went along.”

In those days I was making it up as I went along, from New Haven and New York, to Boston and Providence. “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, / But to be young was very heaven.”

SI: It sounds idyllic. And yet you seem to have left Yale, and enrolled at Goddard College, a place renowned for experimentation. How did this move come about?

JC: Like Shelley and so many others, eventually I had to “come down,” not to London, but to the real world. I simply hadn’t kept up with the work. (Oddly, I remember passing a class in logic, and failing one in existentialism.)

In those days, what would happen next was quite clear. Not staying in college or grad school, or not having majored in a hard science, meant that you were basically cannon fodder. You could be called up anytime the draft board back home needed a few more bodies to meet its monthly quota.

SI: So, before you even went to Goddard, the military called you. How long did you serve, and in what capacity? And how did this experience affect your writing journey?

JC: Shortly after I left Yale for the last time, in the early summer of 1961, things were heating up. Vietnam had been wobbling since the fall of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the Berlin Wall was going up, and Khrushchev was pounding his shoe at the UN.

Bomb-shelter directions were posted in the subway stations; schoolkids were being taught how to duck. The future had never been so bleak. My first wife and I were married in December 1961. To tell the truth, things seemed so bad that we were not sure there would even be a future. We had just driven cross-country to San Francisco when my draft notice arrived. Remarkably, we were able to skate through those next few years and come out reasonably well. Chalk it up to Dame Fortune. I certainly sweated through a few spins of the wheel.

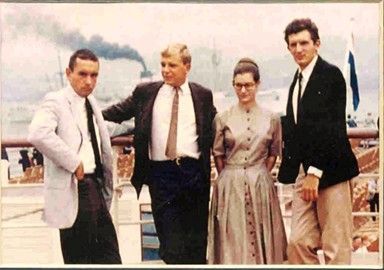

After boot camp at Fort Leonard Wood, and additional training in Georgia, I found myself in the Signal Corps, and unbelievably lucky to have been assigned to a company stationed in Fontainebleau, France. Not long after I got there, my wife was able to come over.

The two of us suddenly being together in France was like a fairy tale. Or a classic Hollywood film about garrison duty in your father’s old regiment in some romantic country. Maybe like the early pages of Joseph Roth’sThe Radetzky March.

Amazingly, I was not in Vietnam, on the other side of the world, where so many of my high-school classmates, and so many Army friends I had trained with, in Missouri and Georgia, had already been sent. Instead I was in what seemed to be, on first glance, some sort of laid-back, peacetime army. The sergeant of my platoon was a Korean War veteran; one of the older men had fought in World War Two.

More than that was the fact that suddenly,

voilà, I was inadvertently following in my great-uncle’s footsteps.

Incroyable! I can still remember that summer day the train from Bremerhaven pulled into the Gare du Nord, and I had my first glimpse of the streets of Paris.

Lafayette,

nous sommes ici!

The truth about being in the Army in France was more sobering. I had become an infinitely tiny, expendable cog in the enormous Cold War standoff between NATO and the Warsaw Pact nations. If the balloon had gone up in Europe on the day I arrived (as it almost did a few months later, in October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis), my signal company would probably have been vaporized. But it never happened.

I was assigned a desk job and quickly learned what was expected of me. Things went well. My wife and I were able to live off post, in a small apartment in the village of By-Thomery, overlooking the Seine, at the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau. It was heavenly.

SI: I bet it was! Tell us more about your experiences in Paris from that time.

JC: A few doors up the street was a boarded-up chateau that had once been the studio of Rosa Bonheur, the celebrated nineteenth-century painter of animals. We managed to get the key. All of her things were still there, as though she had just put down her brush, and gone out into the garden.

In a cemetery nearby were the graves of Katherine Mansfield and the mysterious Armenian mage, Georges Gurdjieff, mentor of Margaret Anderson, Jane Heap, and Jean Toomer. A short drive through the forest took one to Barbizon, a cradle of pre-Impressionism, much loved by Millet, Corot, and Rousseau, and later frequented by Monet, Renoir, and Sisley.

Almost every Saturday morning we walked through the forest to the local station and boarded the train to Paris, to visit the churches and museums. For dinner that evening, in some small Algerian cafe on the Left Bank, we could each have a pris fixe of couscous, demi baguette, and wine, for five francs—about one American dollar.

In the winter, sometimes on an early Sunday morning, there seemed to be no one else in Louvre except the attendants. We could enter the completely empty Grande Gallerie, nod to the guard, and come up to within a few feet of the Mona Lisa.

I remember one time we were walking along with an elderly couple from San Francisco, friends and aficionados of Paris who were trying to find the storefront where the original Shakespeare and Company had been. They had known Sylvia Beach back in the 1920s. Coming along the sidewalk was this man about their age, with flowing white hair, in a white toga, and sandals made from flattened sections of a truck tire. “Raymond!” they called out. It was Raymond Duncan, Isadora’s older brother, who must have been in his eighties, and whom they seemed to have known in San Francisco back in the old days. They had not seen him since the war ended.

Raymond was delighted to see them, and to meet us, and began explaining that on August 24, 1944, the night before the Allies liberated Paris, he and a friend had gotten a couple of revolvers and climbed to the top “of that building, over there,” and had taken potshots at the frantic German soldiers moiling below. (He may have said the other person was either Jean Paulhan or Jean Cocteau, but I can’t remember now.)

On another occasion, in a different country, one morning in Venice we had taken a boat to the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni on the Grand Canal, hoping to be admitted to the Guggenheim Collection of Art. Out front was Marino Marini’s large bronze sculpture, “The Angel of the City,” consisting of a nude male figure, with outstretched arms, astride a horse. When we knocked on the door, Peggy Guggenheim herself appeared; the museum was just opening. She was holding a large metal phallus and proceeded to fit it into the correct place on the male figure. “I can’t leave it out here overnight,” she said. “Someone would steal it.” Then she invited us inside to see her collection.

Such adventures and encounters seemed never-ending. During scheduled military leaves, we managed to explore the Ile de France, the Lowlands, Italy, and the UK. In our last year we acquired a 1949 Citroen Quinze, a classic French automobile with front-wheel drive. (It was the getaway vehicle of choice in French gangster movies.) The crankcase held nine quarts of oil, the fenders were solid chrome, and two could sleep quite comfortably in the back seat. We drove it to Amsterdam and back, and from one cathedral town to the next.

When my time was up in early 1964, we didn’t return to the States, Instead, the two of us, carrying knapsacks and staying in youth hostels, hitch-hiked all over Europe—down the length of Italy and around Sicily, and from Greece and Spain to Edinburgh, Glasgow, and the Lake Country.

We had rolled the dice, then, during an extremely troubling, nerve-wracking time. When called, I had served my country; fortunately, my time in the military had turned out to be unbelievably positive. If only every aspiring writer might have such good fortune.

SI: Indeed. What brought you back to the States and to Indiana?

JC: We had managed our Grand Tour of seven months on a remarkable $5 a day for the two of us, but by mid-October we were broke, and we needed a rest. As for returning to Indiana, I think I had hoped to follow in the footsteps of William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, and Flannery O’Connor, who had done all right by sticking fairly close to home and writing about what they found there.

SI: Many aspiring writers of your generation pursued jobs in academia by enrolling in MFA programs, which were starting to appear on the nation’s campuses at about the time you left college. Were you ever interested in doing that?

JC:

Mark Strand, originally from Canada, was a grad student in the art school when I was at Yale College. He and a former roommate and pal of mine, Al Lee, were active in poetry circles on campus, and in 1960 they decided to go out to Iowa City and do poetry. They roomed together for a while out there. There was no way I could have gone with them. I had no money, and in those days I was trying to write fiction. I had won a nice poetry prize at Yale in my last year there, but poetry was far from my mind. My models back then were Faulkner, Hemingway, and Nelson Algren, none of whom had ever spent much time in a classroom.

Earlier, you asked about how I had enrolled at Goddard College. By 1967, back from Europe, I had G.I. Bill benefits, and thought I ought to finish up and at least get a B.A. degree. I was involved in protesting the war in Vietnam and had little free time. It made sense to enroll in Goddard’s non-residential program. I had to do three six-month cycles; it took a year and a half.

Goddard, with its emphasis on individual course of study and group discussion, was a marvelous place. Every six months one spent a couple of weeks in the Vermont woods, sitting in a circle with people who were seeking alternatives—in life, in learning, in service to others. It was definitely worthwhile. But I had to put food on the table. By the time I graduated, in early 1969, I had already found a job in book publishing in Indianapolis.

SI: What did you do in the publishing industry? Was the work congenial? Did you do any writing?

JC:

I had already worked for a daily newspaper, so becoming an apprentice in the world of book publishing was not difficult. It turned out to be a wonderful place to learn. Bobbs-Merrill was an old-line publishing house, traceable to the 1850s, and the first such establishment west of the Alleghenies. By the 1970s it was the only publishing house in the country that conducted all phases of book production—raw manuscript to warehouse, and everything in between (except for typesetting)—in a modern, centralized plant in northwest Indianapolis.

Initially, I spent a couple of years in the boiler room, blue-penciling manuscripts. By 1973 I had another stroke of luck and was hired as managing editor of Bobbs-Merrill’s college division. I supervised the copyediting, proofreading, design, and production of texts primarily in the arts and humanities. The college division published about a book a week, and the entire company, called Howard Sams—consisting of college, law, children’s, technical, and trade divisions—published about a book a day. It was a great place to be, with a proud tradition of making books—books that had won Pulitzer prizes, and books that had sold in the millions. In the 1950s, the New York office had employed people like Hiram Hadyn, Louis Simpson, and Edward Gorey. It was a wonderful tradition to be part of.

In the Indianapolis plant, I could step out of the front office, wander across the factory floor past all kinds of web and flatbed presses, stapling- and perfect-binding machines, paper cutters and trimmers, all of which would be thundering away—and even a quiet, old-fashioned hand bookbindery—and go on out to the warehouse, and chat with the fork-truck drivers, who were stacking skids of finished books I had worked on.

It was an extremely rewarding job, one that involved a lot of writing—internal reports and recommendations, jacket copy, endless memos, correspondence with the authors, queries to copyright holders. I learned a great deal about writing and publishing from a host of talented colleagues—especially the director, a Marine Corps veteran and old publishing hand, who had gone to Harvard with the Kennedys.

SI: Did you come into contact with other poets who encouraged you or read or commented on your work in those days?

JC: My first day at Bobbs-Merrill in 1969 I wrote the dustjacket copy for the trade edition of Naked Poetry, and a few years later I supervised the production of a companion volume, New Naked Poetry, both compiled by Steve Berg and Robert Mezey.

There were trade and textbook editions of both books. They had silly titles but were serious collections, and quite successful. I got to know Steve Berg, Mezey less so. One day when I was in Philadelphia, Berg mentioned that he was going to launch a tabloid-sized magazine called American Poetry Review. He did, and it was a smash hit. (I never published in it, though.) By this time I had pretty much given up on fiction, after an agent in New Jersey had lost the original manuscripts of a bunch of short stories I had trusted him with. (I still have the carbons.)

This was in the early 1970s, right about the time of the fall of Saigon, and Nixon’s resignation. While working to produce those two poetry anthologies, and a third one compiled by Bill Heyen, I was in contact with a considerable number of contemporary American poets—Ginsberg, Bly, Kinnell, Levine, Levertov, Stafford, Creeley, Knight, Levis, McGrath, et al. I didn’t really get to know them at the time, although I was to meet most of them later on, in the 1980s. But I got a close look at their different manuscripts, with all their corrections and squiggles and marginal notes.

I should mention here, too, that I had become a father in 1969, that my marriage was on the skids, and that there was considerable conflict at home. Which led, eventually, to a divorce in late 1974. I didn’t do much writing of my own during those Watergate years, but at odd moments I kept trying. And things really weren’t all that discouraging.

By the time Gerald Ford was president, I was writing more, and beginning to read a few of my poems at a local hang-out in Indianapolis called the Hummingbird Cafe. I gradually became acquainted with two very different poets, Jim White and Etheridge Knight, who were already publishing their own books, and who gave me encouragement and advice—about writing, and about reading in public.

Such connections and influences increased my interest in moving from fiction to poetry. That impulse got a big boost in 1975 when

The Nation published my poem “Early Warning.” After that, it was off to the races. The Walt Whitman award came five years later.

Another important part of that transitional decade was my meeting the young woman who became my present wife, Diane Haston. Her father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, as it turned out, had all been builders and contractors. (Their specialty, following the Civil War, had been barn-building.)

In 1976, with her support and encouragement, I left Bobbs-Merrill to try my luck as a freelance copyeditor and interior book designer. I gigged around for a few years in greater Indianapolis, and was fortunate to find part-time work with the newly formed Hackett Publishing Company.

By this time I had settled down somewhat, become a weekend father, and bought an old Victorian house (a fixer-upper, in the heart of the inner city, on the Near Eastside)—all of which may have had some sort of stabilizing effect. I had begun to think about writing what I hoped might be considered serious poetry.

SI: Now we get down to it. Please describe the process leading up to publication of your first book, Work, for the Night is Coming (1981), by Macmillan, and to its receipt of the Walt Whitman Award.

JC: It was simple. Laura Gilpin, whom I didn’t know and never met, had won the Whitman Award for a first book in 1976, and she was from Indianapolis. So it was possible. I entered the contest three years in a row, and kept trying to improve the manuscript, adding new poems and taking out inferior ones. The third time, in 1980, it was selected, from among 1,100 other entries, by Galway Kinnell.

Enormous changes followed. It was like shifting to warp drive. There were over a hundred different reviews, all favorable, notably in the New York Times Book Review and the New York Review of Books. (The latter by Helen Vendler, whom I was to meet later on, when she arranged to fly me out for lunch at the Harvard Faculty Club, to interview for a job at Harvard.)

SI: And right here, with this first volume, Mississinewa County is born. The book is full of what we have to assume are local references, in poems based on clear and direct observation, but often with a discursive quality. At this early stage as a poet, why were you so compelled to give your surroundings a “local habitation and a name”?

JC: There were precedents, definitely. Think Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha County. Ross Lockridge, Jr. and Raintree County. Goldsmith’s deserted village.

SI: But how important should rootedness, or a sense of place, be to a working poet?

JC: For a few developing writers the old home place is important, for some, not so much, for others not at all. It’s hard to predict. In my case, professors at Yale, on learning of my writing ambition, advised me to go out into the world and experience something first-hand. They really didn’t say anything about going home again.

“It doesn’t matter,” they said. “Go find something to do. Anything. Anything at all, as long as it’s a safe distance from this campus.” They pointed at the gothic windows of the Saybrook College dining hall. “Go out west and work on a ranch,” they suggested. “Become a war correspondent. Start a mushroom farm. Whatever you do, whatever happens to you, that will be your material,” they said.

SI: Poems like “For Jack Chatham,” “The Madhouse,” “The Undertaker,” from that first book—were they all based on real events?

JC: Maybe what you’re asking about is the authenticity of such poems. They seem effortless and natural, so did the events they describe “actually” occur? But that’s the very illusion one must learn how to create. Somewhere Auden says that too many poets concern themselves with originality, when they ought to be concerned with authenticity. But how is it achieved?

I’m certainly no expert. In my own case, largely because I had been trying to write fiction for so long, I had already invented and populated Mississinewa County, many years before, even when I was living in France. In my mind, it was already a “local habitation.” There was a lot in the pipeline.

So my archives already contained this backlog—the submerged part of the iceberg—of names, places, tales, stories, genealogies, biographies, even a map, all intended for the fictional evocation of that Mississinewa world. I had been making notes on that sort of thing ever since I left New Haven. It was, in a word, very Faulknerian.

I realized, thanks to my long apprenticeship, that when I finally had a bit of success with free verse—which everyone else was writing at the time, all those well-known, successful poets in those three anthologies—I could use some of that stuff in my poems. By this time, of course, I was forty years old. Half my life was already over. It was time to do something.

SI: You sure did. And then, twelve years later, your next book came out: After the Rain (1993), which won the Poets’ Prize. Just as Frost made an advance on American narrative poetry between A Boy’s Will (1913) and North of Boston (1914), so, in your second book, you achieve full maturity in this form. You also showed what can be done with the extended meditative lyric.

Because I’ve included “Barn Siding” in my anthology for Franciscan University Press (The Colosseum Book of Contemporary Narrative Verse, 2025), naturally I must ask you about it. How did you get the idea to write about the incident in the poem? Can you describe the form you chose, and how you arrived at it?

JC: As with any writer, it’s not so much “where do you get your ideas.” If one can be said to “get” ideas at all, it’s mainly from having read a mountain of books, and from paying attention to what other people say. When it comes to technicalities, however, I will acknowledge that if you look closely at “Barn Siding,” which is a fairly long poem of 650 lines, you’ll notice that every line contains nine syllables. Why did I do that? Where did I get that idea? Why not ten? Or eight? Is it some sort of structuring device? Not likely.

It’s nothing, really. It wasn’t an idea that I “got” somewhere, in a workshop or out of a manual. It was just something I decided to do, maybe to see how it would turn out. Technically, it’s simply syllabics. There’s natural speech rhythm in those lines, but no meter. I may have chosen nine because I was bored from counting pentameter lines to see if they all contained ten syllables. Usually, then, the answer to the question, where or how did you get this idea, or that feature, is—someone told me. Or, I just made it up, on the of the spur of the moment. It’s nothing special.

As for the “idea” or “concept” of “Barn Siding,” there again, it was simply the result of having listened to someone else. I had this favorite uncle—my mother’s older brother. A defrocked Nazarene Church minister who for a second career had established a shop filled with farm antiques in a pole-barn in the unincorporated crossroads hamlet of Plumtree, in the south of Huntington County, not far from the reservoirs.

This uncle had always been a storyteller. He told me once that he had climbed up to the loft of an abandoned barn and was sliding out the floorboards when the whole thing began to shake and started to collapse, and almost killed him. I took that incident and developed it.

(Had my uncle been stealing those loose boards, like the narrator in the poem? One must be cautious with such terms. My uncle did in fact have many fabulous things in that King Tut’s Tomb of a shop in Plumtree. My father, who in his retirement refinished furniture and sold a few antiques of his own, bought several remarkable things from his brother-in-law in Plumtree. I, too, managed to “relieve” that uncle of—and most certainly did not “steal” from him—a museum-quality Jacquard coverlet dated 1846. It just happened to be there, in his barn, and I just sort of slid it out, for a few hundred dollars.)

SI: Wonderful. Now, can you talk about how form corresponds with meaning in your narrative poems? Does form help you find what you want to say, or is it more that you go in with a clear vision or outline of what you want to accomplish with each poem—topically and structurally?

JC: With all due respect, none of that. I may sense notions, or clues, or whisperings, but I don’t begin with ideas. The truth is that I make poems the same way my father built houses and bridges, and the same way my mother made a few dollars by standing near the casket, or next to the bride and groom, and singing her heart out.